Once upon a time, a gloomy old philosopher named Faust observed that his life devoid of meaning. Just as he was about to poison himself, he heard happy voices outside singing Easter hymns. Faust considered turning to prayer. Instead, a stranger named Mephistopheles appeared as an evil spirit sent from Satan. The two made a bargain: Mephistopheles would give him youth and worldly pleasures if Faust would give him his soul in death.

In German folklore, the name Mephistopheles is associated with the Faust legend (Goethe, 2001) that represents someone who comes to a crossroads in life and trades their soul for the obvious esteems of youth, knowledge, wealth, power, acceptance, and so forth, even love. Just for a minute, suppose meaning in life is found in

unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. Would we be truly fulfilled? Solomon, King of Israel, was the wealthiest and wisest man of his time (1 Kings 3:12-13). Yet, despite his wealth and power, he describes these things as empty and meaningless. Jesus asks, “What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul?” (Matthew 16:26).

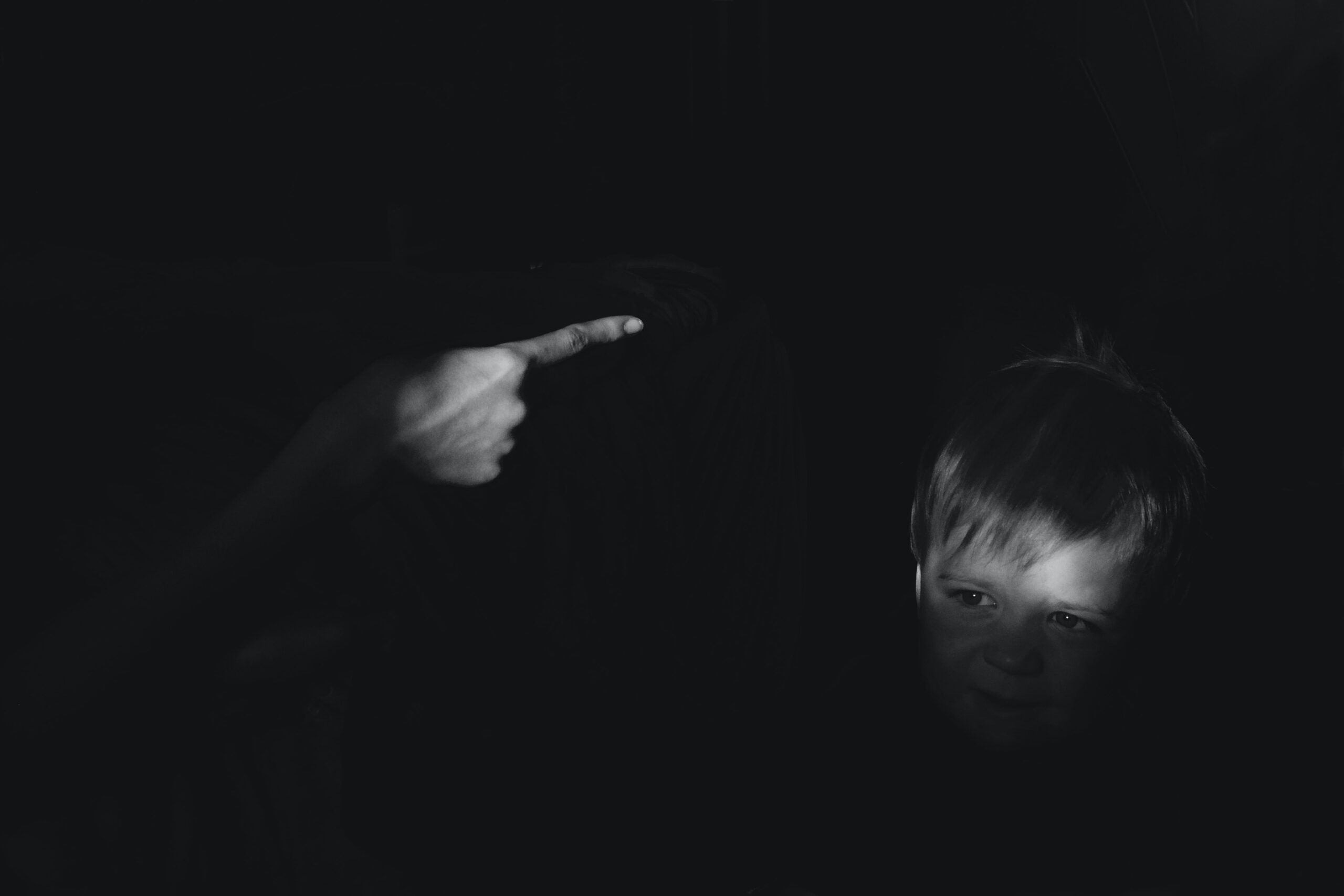

Photo by Maria Brauer on Unsplash

Photo by Maria Brauer on Unsplash

“Two souls live in me, alas, Irreconcilable with one another.” ~ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Karen Horney (1991) uses Goethe’s depiction to explain a range of psychological conditions; for example, depression, anxiety, obsessive behaviour, hypochondria and so forth, that result from trading our souls. She uses the term neurotic, a word that has been in use since the 1700’s to describe someone who displays drastic and irrational reactions to manage their anxiety (known today as a psychological disorder; for example, an Anxiety Disorder). Like Faust, Horney believes the neurotic makes a pact with devil by trading dependence on God for perfection and pride. Horney sees the neurotic’s stance as, “I can make life work by my own efforts. I don’t need to depend on God.” She (1991, p. 34) explains:

All the drives for glory have in common the reaching out for greater knowledge, wisdom, virtue, or powers than are given to human beings; they all aim at the absolute, the unlimited, the infinite. Nothing short of absolute fearlessness, mastery, or saintliness has any appeal for the neurotic obsessed with the drive for glory. He is therefore the antithesis of the truly religious man. For the latter, only to God are all things possible: the neurotic’s version is: nothing is impossible to me. His will power should have magic proportions, his reasoning be infallible, his foresight flawless, his knowledge all encompassing. The theme of the devil’s pact…begins to emerge. The neurotic is the Faust who is not satisfied with knowing a great deal, but has to know everything.

According to this description, we are all neurotic on some level!

Rejection of Legitimate Needs

Growing up, many of us learn to create a self that can survive the unhappiness of lack of nurturing and rich connection. It begins like this: I approach my parent for comfort and consistently get rebuffed with statements like:

“Leave me alone, Darling. Can’t you see I’m busy.”

“What do you want now?”

“Why are you always so needy?”

“Can’t you leave me alone for a second?”

“Big boys don’t want to be held all the time.”

“That’s sissy stuff.”

“Stop crying.

To deal with feelings of rejection and undesirability, I do not see my parent’s shortcomings. Instead, I turn the pain against myself in an attempt to minimise or dispense with my legitimate need. According to Townsend (1996), this begins a cascade:

-

- My needs for attachment, connection and comfort go unmet.

- I experience injury to the soul that includes lack of love, lack of the ability to parent well and lack of relationship repair, as well as external trauma and painful events. All this leads to the development of shame.

- I make legitimate needs bad (Jesus validated our neediness in Luke 4:18). I blame the need rather than the parent(s) who did not meet the need. Children cannot tolerate the idea that parents could be failing them, so they blame the need.

- I deny my needs. When my heart is isolated and injured, it not only blames the need but then denies it. My injured soul demands that I forget this “troublesome” part of me.

- I develop false solutions. I fashion hiding patterns that help me survive the loss of relationship.

- I produce bad fruit. When my needs are not met, I will experience problems in life and relationships; for example, depression, anxiety, panic, marriage difficulties, addictive behaviours, etc cetera. Luke 6:45 says, “The good man brings good things out of the good stored in his heart and the evil man brings evil things out of the evil stored in his heart. For out of the overflow of his heart his mouth speaks.

Photo by Artyom Kabajev on Unsplash

Photo by Artyom Kabajev on Unsplash

“The key problem I encounter working with wounded, depressed, and unhappy people is a lack of connection…starting from a disconnection from themselves and then with others.” ~ David W. Earle, Love is Not Enough

John Bradshaw (1991, p. 3-4) clarifies:

Since one’s inner self is flawed by shame, the experience of self is painful. To compensate, one develops a FALSE SELF in order to survive. The false self forms a defensive mask which distracts from the pain and the inner loneliness of the true self… When we experience emotional injury, fear, shame, or pride, our first impulse is to hide the hurting parts of ourselves from God, others, and even ourselves.

In other words, shame makes us hide our true selves – those parts of us that are deemed unacceptable.

Therefore, not only do neuroses originate in false self, they are defences against shame. Brené Brown (2012, p. 70) defines shame as, “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging.” Someone has said that neurosis is like hanging on to a hot stove, because if we remove our hands we may not get dinner. We hang on to that which torments us because without it we do not believe we will survive.

In Horney’s terms, we turn against the self, thereby warding off the anxiety that would be engendered if we felt our true personhood was being seen. We reject the notion that our developmental needs were genuine and reasonable and still view ourselves as unacceptable to those we need most, our primary caregivers. If we shut off parts of ourselves (to lower our parents’ anxiety) it provides a sense of control that allows us to continue to view our parents as good and to protect our attachment ties. This becomes our template for relating to ourselves and others. However, the solutions we construct often alienate us from ourselves and authenticity.

Strategies of Disconnection

Photo by Fred Moon on Unsplash

“Rationalization may be defined as self-deception by reasoning.” ~ Karen Horney

Evidently, we adopt neuroses because we are attached to our survival strategies, even though they create disconnection and distress (known as psychological disorders). “The problem is,” according to

Townsend (2001), “that when we hide our injuries and frailties, we run from the very things we need to heal and mature. What served as protection for a child becomes a prison to an adult.” Bradshaw adds, “After years of acting, performing and pretending – one loses contact with who one really is. One’s true self is numbed out.” As adults, our true self is suppressed and we relate from a false self. In other words, we exchange our soul for the belief that we can make life work by our own efforts. We don’t need to depend on anyone, especially God.

Horney organises neuroses into three categories or patterns of behaviour based on universal needs that have been disparaged. Barry (my husband) explains:

My unacknowledged universal need for closeness and connection are intense and if these needs are not met there is significant anxiety. The nature of my need tends to be unrealistic and too central to my existence. This distortion occurred during my early development when legitimate needs were not met. They stem from my perceptions (not necessarily my parents’ intentions) of lack of deeply conveyed love and all-encompassing protection. Both of these needs were perceived as conditional, based on my adherence to the family values. I adopted survival responses to handle these parental conditions to cover the deep shame I felt about my acceptability.

As adults, we elicit relational responses consistent with our childhood template; for example, in the early days after Barry and I met, deep down we knew the other was incapable of being emotionally responsive. Therefore, we anticipated rejection even though neither of us had responded in a rejecting way. We presented to each other our versions of old relational patterns where we could anticipate and reject our needs consistent with our childhood responses.

In order to cope with the pain of unmet needs, we adopt three primary survival strategies to help us rise above and indirectly fulfil them. Three Strategies of Disconnection or Shame Shields (Brown & Hartling, 2016) that serve as self-protective armour are:

1. Moving Away (withdrawing). The problem of parental indifference is “solved” by withdrawing from family involvement into the self and by hiding, silencing ourselves and keeping secrets. We eventually become sufficient unto ourselves by believing, “If I withdraw, nothing and no one can hurt me.” As adults, legitimate needs change into the need for self-sufficiency, independence, to never need anyone (we tend to refuse help and are often reluctant to commit) and/or the need for perfection and unassailability, to never make a mistake and to be in control at all times.

2. Moving Toward (seeking to appease and please). Most children are overwhelmed by a fear of helplessness and/or abandonment. For the sake of survival, hostility towards less than nurturing parents must be suppressed and the parents won over. If this works the compliance coping strategy becomes the preferred coping style that believes, “If I can make you love me, you will not hurt me.” As adults, legitimate needs change into the need for affection and approval, to please others and be liked by them, the need for a partner, or someone to take over their life (“love will solve all my problems”) and/or the need to restrict life to narrow borders, to be undemanding, satisfied with little and to be inconspicuous.

3. Moving Against (trying to gain power over others, being aggressive and using shame to fight shame). Horney observes that some children’s reactions are not stereotypically weak or passive, but more a response like “basic hostility” that leads to an effort to protest injustice. Over time a habitual response to life’s difficulties develops; such as, an aggressive coping strategy that believes, “If I have power, no one can hurt me.” As adults, legitimate needs change into a desperate need for power and control over others, a façade of omnipotence (often contempt for the weak and a strong belief in my own rational powers), a need to exploit others, get the better of them, or use people and a need for social recognition and prestige. They are often overwhelmingly concerned with appearances and/or popularity based on the fear being ignored, being thought of as plain, “uncool” or “out of it”. Other legitimate needs change into a need for personal affirmation, based on the fear of being a nobody, unimportant or lacking meaning and substance and/or a need for personal achievement, being number one at everything and devaluing anything they cannot achieve.

Photo by KS KYUNG on Unsplash

Moving away was my chosen Shame Shield. My pact with the devil took the form of a vow, “To need is to be hurt, therefore, I will never need people again.” I believed life would work best if I withdrew either physically, emotionally, or both. To others I appeared calm and competent. However, painful feelings, anger and distress were internalised and I imploded and collapsed inside. My shame shield acted to hide and camouflage any needs. Secretly I believed my very existence was a burden to others, therefore, no one would ever see my internal suffering or my deep longing to be loved and to be desired for who I am.

Moving toward was Barry’s chosen Shame Shield. His closed down parts were expressed by emotional detachment that helped protect him from unwanted drama, anxiety, or stress. But his uncomfortable and hurtful silences damaged his relationships, stunted his personal growth and left him feeling resentful that his moving towards was not reciprocated. His deep longing was to be accepted for who he is without having to earn it.

Moving against was Mitchell’s chosen Shame Shield. Unable to connect with his inner world, his stuck tears led to aggression (Neufeld, 2010). Sexually abused by a neighbour as a five-year old, Mitchell stuffed his legitimate responses so far down, that as an adult he was unable to contact them. He found himself in court after assaulting a man in an altercation. “When something is not working for you and you can’t feel sadness and disappointment, you go into a foul mood and attack verbally or physically”(Neufled, 2010). Mitchell’s un-cried tears not only increased his anxiety, stress and aggression (Frey, 1985), they moved him towards isolation rather than connection (Nelson, 2009). Even though his deep hunger for connection made him capable of loving and being loved, it also made him capable of wounding and being wounded. Mitchel’s deep longing (often denied) is to be seen and understood.

Even though we use all three strategies, we tend to lean towards one in particular. Despite being shame shields designed to protect us, they tend to engender more pain. Alice Walker (1990, p. 353) explains:

In blocking off what hurts us, we think we are walling ourselves off from pain. But in the long run, the wall, which prevents growth, hurts us more than the pain which, if we will only bear it, soon passes over us. Washes over us and is gone. Long will we remember pain, but the pain itself, as it was at the point of intensity that made us feel as if we must die of it, eventually vanishes. Our memory of it becomes only a trace. Walls remain. They grow moss. They are difficult barriers to cross, to get to others, to get to closed down parts of ourselves.

Even though there are exceptions, we tend to choose careers that are congruent with our chosen interpersonal style of relating or our strategy of disconnection. This way we can feel special and enjoy substantial secondary benefits (this is why it is so hard to recognise or acknowledge). Our chosen strategy can become the basis of our identity and the primary source of our self-esteem; for example, Barry’s moving towards worked for him in accountancy, as people viewed him as responsible, dependable and kind. As such, we experience false pride and sense of entitlement from others; for example, the defence of moving towards demands unwavering approval.

Knowing our primary strategy of disconnection makes it easier to understand our adult experience, because the way we relate is a representation of our past experiences. Thus, we cannot live in the present moment, as we are continually responding to our past. As Richard Rohr (2003) explains:

If you are not trained in how to hold anxiety, how to live with ambiguity, how to entrust and wait, you will run, or more likely you will “explain”. Not necessarily a true explanation, but any explanation is better than liminal space. Anything to flee this terrible” cloud of unknowing. Those of a more fear-based nature will run back to the old explanations. Those who love risk or hate thought will often quickly contrast a new explanation where they can feel special and again in control.

Photo by Road Trip with Raj on Unsplash

Photo by Road Trip with Raj on Unsplash

“When I was beleaguered and bitter, totally consumed by envy, I was totally ignorant, a dumb ox in your very presence.” ~ Psalm 73:21-26 TM

The Devil’s Pact and Repentance

The real instigator of our shame and disconnection strategies is the devil. He loves them, as they allow him to make a pact with us that can take us out. The devil’s pact is to lie to us that we will find life through our own efforts. We do not need to depend on God, because we are God. Satan whispers lies into our early wounds, establishes a stronghold and ensures that we relate using our chosen Shame Shield. Most of us are unaware of the extent of our bondage. We know little of abundant life and there are levels of freedom, joy and rest we have never enjoyed because we are committed to our own survival strategies for finding life. Jesus teaches that mental and emotional problems; such as, anger, worry, and desolation, stem from our deep thirst. These are spiritual problems that originate in the heart of inmost being (Mark 7:14-23).

So, how do we find meaning in life? Henri Nouwen (1979) claims that nobody escapes being wounded. “The main question is not ‘How can we hide our wounds?’ so we don‘t have to be embarrassed but ‘How can we put our woundedness in the service of others?’ When our wounds cease to be a source of shame and become a source of healing, we have become wounded healers.” How do we exit the devil’s pact and make our woundedness a source of healing?

Part of the answer may lie in Luke 10:17-20 (MSG) that describes a cluster of believers returning from a mission trip where Jesus had commissioned them to go in His name, with His authority:

The seventy came back triumphant. “Master, even the demons danced to your tune!” Jesus said, “I know. I saw Satan fall, a bolt of lightning out of the sky. See what I’ve given you? Safe passage as you walk on snakes and scorpions, and protection from every assault of the Enemy. No one can put a hand on you. All the same, the great triumph is not in your authority over evil, but in God’s authority over you and presence with you. Not what you do for God but what God does for you—that’s the agenda for rejoicing.”

Clearly, God has not left us alone to deal with Satan over whom we are powerless. The passage indicates that Satan recognised the missionaries’ authority over demonic powers and fell like “a bolt of lightning out of the sky”. There is no power in our own authority, only in His. Our triumph rests in not what we do for God, but what God does for us. Freedom is ours for the taking. The same God who saved us eternally has the power to save us internally. He desires wholehearted healing.

Photo by Max LaRochelle on Unsplash

Photo by Max LaRochelle on Unsplash

“Seize

Bolts of lightning from the sky

And plant them in fields of life.” ~ The Condemned Apple: Selected Poetry

But there is tension between now and not yet, as complete wholeness is the prerogative of Heaven. While we wait, we suffer the tyranny of the inmost being – unsatisfied longings that tear at the soul. We retreat into strategies of disconnection that kill our desire to love well and kill our desire for God. Yet Jesus, recognising our deep thirst and our bruised and broken hearts, invites us to come and drink freely from the Water of Life. Freedom and wholeness are only found in Christ, the source of Living Water and nowhere else.

Wholehearted Freedom

It is dark when I rise. As I sit with God in the stillness, I glance out the window and glimpse the first light of dawn. The flashing light of a plane across the sky emerges from the darkness. I’m taken back to the multitude of times I have returned home in dawn’s early light from some other continent. My heart leaps and my eyes become moist. I am full from pouring my heart out to others. Now I can rest because I’m home. As beautiful as the world is, home is the best place. “Return to your rest, my soul, for the Lord has been good to you” (Psalm 117:7).

Wholehearted freedom or inner healing is like coming home. It is when we are no longer defined by nor hide behind our Shame Shields. We are able to offer our true selves to healing the world. The movement toward freedom is at the heart of the spiritual journey and the Scriptures speak powerfully into thirsty, broken hearts. Wholehearted freedom is being:

- Completely given over to God

- Loving others well

- Feeling secure in our inner being

- Free from self-protection

- Free from others’ expectations

- Responsive to God’s Spirit

Closing Thoughts…

We adopt Shame Shields or Strategies of Disconnection because we were wounded as children. Our needs for nurturing and to be seen, heard, enjoyed and loved were not met and it was painful. Instead of turning to a good and loving God, we made a pact with the devil that we would make life work on our own terms. Our chosen survival strategy works for a time, but fails to deliver what we ache for most – to be seen, heard, enjoyed and loved for who we truly are.

According to the Christian faith, the meaning of life is ultimately found in Jesus Christ. In him, the questions about meaning and purpose in life are answered with deep hope. We are created by our heavenly Father to reflect His glory, walk in His love, and do His will. Our true identity and meaning are found in being a beloved child of God.

Recently, I came across an article, God Can Heal the Wounds and Scars of the Past, written by Charles Swindoll (adapted from Swindoll, 1994, 410–411). Swindoll eloquently answers the weighty question of whether God is interested in freeing us from the devil’s pact:

Tucked away in a quiet corner of Scripture is a verse containing much emotion: “From the city men groan, and the souls of the wounded cry out” (Job 24:12). The scene is a busy metropolis. Speed. Movement. Noise. Rows of buildings. Miles of apartments, houses, restaurants, stores, schools, cars, bikes, kids. All that is obvious, easily seen and heard by the city dweller.

But there is more. Behind and beneath the loud splash of human activity are invisible aches. Job calls them “groans”. That’s a good word. The Hebrew term suggests that this groan comes from one who has been wounded. Perhaps that’s the reason Job adds the next line in poetic form, “the souls of the wounded cry out”. In that line, wounded comes from a term that means “pierced”. But he is not referring to a physical stabbing, for it is “the soul” that is crying out.

Job is speaking of those whose hearts have been broken… those who suffer from the blows of “soul-stabbing” which can be far more bloody and painful than “bodystabbing”. The city is full of such sounds—the wounded, bruised, and broken, crying out in groans from the heart.

That describes some of you, I am certain. You may be living with the memories of past sins or failures. Although you have confessed and forsaken those ugly, bitter days, the wound stays red and tender. You wonder if it will ever heal. Although it is unknown to others, you live in the fear of being found out… and rejected.

Others of you may be “groaning” because you have been misunderstood or treated unfairly. The wound is deep because the blow came from one you trusted and respected. It’s possible that the hurt was brought on by the stabbing of someone’s tongue. They are saying things that simply are not true, but to step in and set the record straight would be unwise or inappropriate. So, you stay quiet… and bleed. Perhaps a comment was made only in passing, but it pierced you deeply.

Tucked away in the corner of every life are wounds and scars. If they were not there, we would need no Physician. Nor would we need one another. Only the Great Physician can turn our ugly wound into a scar of beauty. Only He can heal the pain and sin in our past and make us whole again. Reflect on Psalm 147:1–5 (NIV):

Praise the Lord.

How good it is to sing praises to our God,

how pleasant and fitting to praise him!

The Lord builds up Jerusalem;

he gathers the exiles of Israel.

He heals the brokenhearted

and binds up their wounds.

He determines the number of the stars

and calls them each by name.

Great is our Lord and mighty in power;

his understanding has no limit.

A Declaration…

I declare that God is a God of healing. He has not left me alone to deal with Satan over whom I am powerless. I declare that my power rests not in my own efforts to self-protect, but what God does in me and for me. I declare that freedom is mine for the taking. I renounce the devil’s pact and embrace true freedom.

A Prayer…

Prayer for Inner Freedom (Denny, 2018).

Lord,

what most often stops me

from achieving freedom

is my tendency to be caught up

in fears and expectations

about what I ought or should be.

My usual automatic responses

tie me down and inhibit me

from exploring new areas of growth.

I ask and pray for a greater sense

of inner freedom and that

I might reach the fresh and challenging

possibilities that You, O God,

want me to realize. Amen.

Reflect…

How might the devil’s pact apply to me?

Which shame shield or strategy of disconnection do I identify with most?

What would healing look like for me?

What do I want to talk to God about?

About the author: Dr. Paula Davis is a clinical counsellor, supervisor and educator specialising in psychological trauma. She has worked in higher education over many years as senior lecturer in counselling. Along with her husband she designs and delivers marriage enrichment/education programs in Australia, Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Europe.

References

Bradshaw, J. (1991). The family: A new way of creating solid self-esteem. Florida, USA: Health Communications.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead (1st ed). USA: Avery.

Brown, B., & Hartling, L. (2016). Shame shields: The armor we use to protect ourselves and why it doesn’t serve us. Retrieved from: https://catalog.psychotherapy.com.au/sq/pz_001195_brenebrown_email-32850

Denny, C. (2018). Prayer for inner freedom. Almost Daily Prayer: Passion for God. Retrieved from https://www.almostdailyprayer.com/2018/07/prayer-for-inner-freedom.html

Fahkry, T. (2017). Why your emotional wounds strengthen you. Mission.org. Retrieved from https://medium.com/the-mission/why-your-emotional-wounds-strengthen-you-4b5dff0cae20

Frey, W.H. (1985). Crying: The mystery of tears. Minneapolis: Winston Press.

Goethe, J. W. V. (2001). Hamlin, Cyrus (Ed.). Faust: A tragedy: Interpretive notes, contexts, modern criticism (Norton Critical ed.). New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Horney, K. (1991). Neurosis and human growth: The struggle towards self-realization (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Neufeld, G. (2010). Transformative parenting workshop. CA, USA:

Nouwen, H. J. M. (2010). The wounded healer: Ministry in contemporary society 2nd ed.). New York: Image Doubleday.

Rohr, R. (2003). Grieving as sacred space. John Mark Ministries. Retrieved from http://www.jmm.org.au/articles/1266.htm

Strong’s Hebrew. (n.d.). Broken-hearted. BibleHub. Retrieved from https://biblehub.com/topical/b/broken-hearted.htm

Swindoll, C. R. (1994). The finishing touch: Becoming God’s masterpiece. USA: Word Publishing.

Walker, A. (1990). The temple of my familiar. New York, Pocket.

Photo by

Photo by

0 Comments