“It’s not what you eat that gives you indigestion, it’s what’s eating you.” ~ Mark Twain

“A part of you was left behind very early in your life: the part that never felt completely received. It is full of fears. Meanwhile, you grew up with many survival skills. But you want yourself to be one… Try to keep your small, fearful self close to you… Let it teach you its wisdom; let it tell you that you can live instead of just surviving. Gradually you will become one, and you will find that Jesus is living in your heart and offering you all you need.” ~ Henri Nouwen, The Inner Voice of Love

“I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry…” ~ John 6:35

They stand one by one. It is impossible to stem the flow. Stories and tears from both husbands and wives, stream like a waterfall. Earlier in the day, the heat suffocating, Barry and I move our chairs to face each other and share our story of past hurt, abandonment and of feeling misunderstood and unheard. Robert (founder and director of Connect for Life) translates. Even though my eyes are fixed on Barry, I hear the pain in the room, the copious tears, the overwhelmed, broken hearts attempting to lean into hope. This is a safe place to reveal and voice stories. Their culture of hiddenness, crammed full of shame, breaks open in this aching space. Our suffering joins with theirs, the wounded healing wounds, our love exploding suffering to bits, the shards of fear, anxiety and sorrow now exposed to the Light.

As we journeyed with these suffering Sri Lankan people and told our story, we shared the familiar ache of worry, fear and anxiety of our past that was acute and debilitating. In 2020, as we face the COVID-19 pandemic, it is a time of intense uncertainty. For most people, the anxiety will be temporary and will decrease over time, especially once the virus abates. However, if we return to ‘normal’ we have missed a powerful opportunity for growth. It connects us with the writings of an unknown author:

Death was walking towards a city and a man stopped Death and said, “What are you going to do?” Death said, “I’m going to kill ten thousand people.” The man said, “That’s horrible!” Death said, “That’s the way it is, that’s what I do.”

So the day passed and the man met Death coming back. He said, “You said you were going to kill ten thousand people and there were seventy thousand killed.” Death said, “Well I only killed ten thousand. Worry and fear killed the others.”

Worry, fear and anxiety expect the worst. In the past, we expected the enemy to act, whereas faith expects God to act. It reminds us of a story about sleeping with bread.

The book, Sleeping with Bread: Holding What Gives You Life (Linn, Linn & Linn, 1995), tells the story of the bombing raids of World War II where thousands of children were orphaned and left to starve. The fortunate ones were rescued and placed in refugee camps where they received food and good care but many fearful, shell-shocked, gaunt orphans lived in terror. Many of these children who had lost so much could not sleep at night. They cried for their parents. Hungry, they cried for food. They feared waking up to find themselves once again homeless and starving and nothing seemed to reassure them. Finally, someone stumbled on the idea of giving each child a piece of bread to hold at bedtime. Tucked in to bed and holding onto their bread, the children could finally sleep in peace. All through the night the bread reminded them, “Today food was provided and I ate; I will eat again tomorrow.” When the bombs fell, bread was a comfort, reassuring the children that they could sleep peacefully.

Source: https://historycollection.co

In my mind’s eye, I see the image of those little war orphans sleeping peacefully in their beds, each holding on to a piece of bread. For those suffering children the bread meant much more than food. Bread was a promise, a sliver of hope. In the midst of a chaotic war-torn world, bread was a reassuring, a tangible presence, the gift of hope for tomorrow. Jesus knew that when that when life makes no sense (as in COVID-19) and I feel overwhelmed, I would only sleep with bread in my hand.

Holding onto Bread

Jesus came to give us bread to hold in our hands while we sleep. He came to set us free from worry, fear and anxiety, but He created us with free minds, with hearts to love unreservedly and with wills that we might obey without stinting. According to Proverbs 23:7, “As a man thinks in his heart, so is he.” Lack of bread is expressed through the torment of our addictions and enslavements (John 8:34). The most universal of all addictions – worry, fear and anxiety rob us of joy. This is pertinently conveyed in the poem, Against Pleasure, by Robin Becker (2006, p. 15):

Worry stole the kayaks and soured the milk.

Now, it’s jellyfish for the rest of the summer

and the ozone layer full of holes.

Worry beats me to the phone.

Worry beats me to the kitchen,

and all the food is sorry. Worry calcifies

my ears against music; it stoppers my nose

against barbecue. All films end badly.

Paintings taunt with their smug convictions.

In the dark, Worry wraps her long legs

around me, promises to be mine forever.

Thugs hijacked all the good parking spaces.

There’s never a good time for lunch.

And why, my mother asks, must you track

beach sand into the apartment?

No, don’t bother with books,

not reading much these days.

And who wants to walk the boardwalk anyway,

with scam artists who steal your home and savings?

Watch out for talk that sounds too good to be true.

You, she says pointing at me,

don’t worry so much.

What kinds of things do you worry about? Some prime examples are:

1. Worrying about whether others like us;

2. Worrying about money and jobs;

3. Worrying about the future;

4. Worrying about people finding out we did something wrong;

5. Worrying about what others will think if us if we do not succeed;

6. Worrying about our spouse; or,

7. Worrying about our appearance and body.

Who can imagine a life without worry? If we spend much time worrying and are anxious about too many things, the enjoyment of life and relationships ceases. Like the war-orphans, we fear losing so much that we cannot sleep at night. Most of us are addicted to worry, fear and anxiety because we simply do not see it as something that grieves God. It has become acceptable and we excuse it without a second thought, because, after all, it is not harmful like addiction to drugs or alcohol!

Worry, Fear and Anxiety Affects our Health

Worry, fear and anxiety can have a powerful impact on our physical and mental health. Physically, worry decreases our immune system making us more susceptible to illness. Worry can increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, digestion issues, muscle tension and headache and can affect our brains leading to disrupted sleep, lack of energy, stiff or painful muscles and an inability to cope with physical pain. Worry can interfere with neurotransmitters: brain chemicals that communicate information throughout the brain and body and can cause adverse symptoms when levels are out of balance (Ayano, 2016).

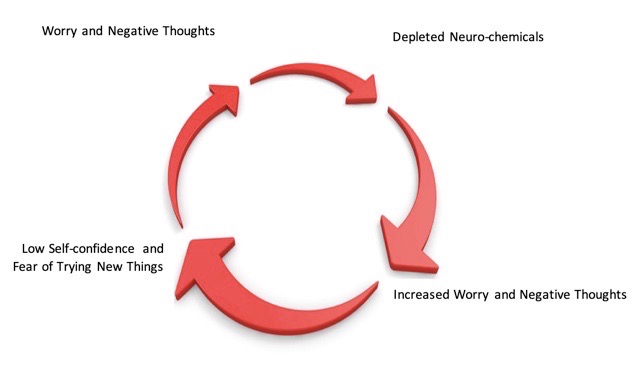

Worry, fear and anxiety can also have a powerful impact on our mental health. Even literature reflects this as Shakespeare (1996, p. 39) observed, “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Milton (2013) commented, “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.” Proverbs 4:23 warns, “Above all else, guard your heart for everything you do flows from it.” Worry causes us to ruminate on negative thoughts, depleting chemicals like serotonin and endorphins that raise our sense of wellbeing. This creates a cycle of negativity and further lowers our neuro-chemical levels, leading to low self-confidence and fear of trying new things. Inevitably, it leads to regret and dejection, thus perpetuating the negative cycle. Eventually, negativity becomes an instinctive habit and our first response to a situation.

The amygdala, a component of the limbic brain has long been linked with a person’s mental and emotional states. Worry and negative thinking constitutes an assault on the heart and the brain. Worry is really negativity expressed by self-disclosure; for example, if I continually say phrases like, “I’m so stressed” or “I’m so overwhelmed,” or, “I’m terribly busy,” I may feel important, but it cuts me off from relationships and the support I really need. It is actually a form of self-abuse – my ears hear it and my limbic system absorbs it. My amygdala listens as I talk to myself and perpetuate lies.

Worry Strangles

Five times in the Sermon on the Mount Jesus tells us not to worry, repeating the same Greek term for “anxious” that means “to divide, to separate.” The English Oxford Dictionary (Simpson & Weiner, 1989) defines “worry” as “the state of being anxious and troubled over actual or potential problems.” The old English word for worry means “to strangle.” Jesus articulates the price disabling worry in Matthew 6:25-34:

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? Can any one of you by worrying add a single hour to your life?

And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith?

So do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the pagans run after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them. But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.”

God never intended His people to become prisoners to worry. Worry easily becomes an energy-draining addiction that Jesus indicates impacts us is in four areas:

- Our values get distorted. Jesus warns, “Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing?” (v.25);

- We become self-focused. We stress about, “What shall we eat?” or “What shall we drink?” or “With what shall we clothe ourselves?” (v.31);

- Our beliefs become distorted over time. Jesus counsels, “For all these things the Gentiles eagerly seek: for your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things” (v.32); and,

- We dread the future. Jesus said, “Therefore, do not be anxious for tomorrow” (v.34).

Living with Doubt and Uncertainty

In one of our countless conversations we try to distill our many trips to Africa, Sri Lanka and India into the essence of what we want to take with us and what we want to leave behind. An example comes to mind from our early morning drive to Delhi airport, the only time India appears at rest. The sun is beginning to rise in soft, pink light through the polluted skies. Our thoughts turn to home as we farewell India and our trip. I lean across to Barry and exhale, “I feel really happy!” Within a minute we slow to pass a dead body sprawled on the road, the result of a motor bike accident with a truck. Disturbingly, there is no covering. No dignity. We are reminded of what Rilke (2020) wrote:

Let everything happen to you

Beauty and terror

Just keep going.

We keep going. In that moment we experience the paradoxical extremes of India – the highs and the lows, the beauty and the heartache. Such a beautiful mess. I concur with Tom Welling (n.d.), “I have so much chaos in my life, it becomes normal. You become used to it. You have to just relax, calm down, take a deep breath and try to see how you can make things work rather than complain about how they’re wrong.”

Doubt and uncertainty make fine bedfellows with worry fear and anxiety because they are rooted in fear. In John Patrick Stanley’s (2005, p. viii) play, Doubt: A Parable, he shares how doubt presents an opportunity to grow:

It is doubt (so often experienced initially as weakness) that changes things. When a man feels unsteady, when he falters, when hard won knowledge evaporates before his eyes he is on the verge of growth. The subtle or violent reconciliation of the outer person and the inner core often seems at first like a mistake, like you’ve gone the wrong way and you’re lost. But this is just emotion longing for the familiar. Life happens when the tectonic power of your speechless soul breaks through the dead habits of the mind. Doubt is nothing less than an opportunity to reenter the present.

Perhaps we struggle with doubt and uncertainty because they raise difficult spiritual questions about pain and suffering. Philip Yancey (1999) in Where is God When it Hurts, proposes three questions no one asks aloud:

- “Is God unfair?”

- “Is God silent?”

- “Is God hidden?”

An old Chinese proverb says, “Deep doubts, deep wisdom; small doubts, little wisdom.” Doubt involves honesty. Doubt forces faith to bedrock. We see contradictions between what we believe and what we experience. We question why things are not turning out the way we were taught to expect. Mature faith does not deny or suppress doubt. Again, Philip Yancey (2000), in Reaching for the Invisible God, writes of Ciszek, a missionary of sorts imprisoned in Russia where he wants to serve God. Yancey writes:

He [Ciszek] realised he had always approached life with an expectation of what God’s will should be, and assumed God would help him fulfill that. Instead, he had to learn to accept as God’s will the actual situations he faced each day, most of which lay outside of his control. Ciszek’s vision narrowed to a twenty-four hour time frame… His book records the agony involved in overcoming doubt and trusting God when everything in his life seemed to argue against it.

Perhaps, in dealing with doubt and uncertainty, the way out is in. Overcoming requires facing doubt and uncertainty head on for, “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties” (Bacon, cited in Wormald, 1993, p. 39). During COVID-19, doubt and uncertainty intensify my soul work, for I have to take what cannot be expelled, explained or reasoned to God to try to make sense of it. I ask for bread to hold in my hand; the gift of hope for tomorrow.

Becoming Bread for Others

All this begs the question: How can I be bread for others? I see the war-weary broken ones standing before us, hungry for that which sustains. Jesus declared, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty… I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever” (John 6:35, 51). What does He mean? Perhaps a clue is found in 1 Corinthians 11:23-24: “The Lord Jesus, on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it, and said: ‘This is my body which is broken for you.’” About to be betrayed, abandoned, killed by the religious leaders of His day, Jesus gives thanks before He gives His life away to free us. I am convinced as I stand before the crowd that what determines a meaningful life is choosing to receive this grace with thankfulness and then giving that grace away. I am blessed so I can bless. Holding onto what gives me life, holding onto fullness, I can come alongside people as they move more fully into who they are meant to be because I hold the Bread of Life in my outstretched hand.

Surrounded by abundance, we in the West tend to live famished lives, anxious and afraid of the threat of scarcity, always groping for more (evidenced by the shortage of toilet paper!) Yet I am finding that there is nothing more powerful than giving ourselves away for others. Abundance and wholeness come from sharing our bread with a broken world. Holding onto bread means I can let Him make my life a gift of bread to satisfy a hungry world.

The fans whir and sweat trickles down my back as the war-trauma stories continue to unfold unbidden. I am bone weary, but in this precious moment while standing in the midst of these ravaged lives, I deeply know that the bread we give is a reassuring, tangible offering, the gift of hope for tomorrow, the gift of hope that assuages the ache of worry, fear, anxiety, doubt and uncertainty.

Later in the year, we smile as we reflect on our last few days in India. Our final workshop is for staff working with slum children in the JanPragati organisation. The leader astounds us with his openness and movement towards being unhidden with his lovely wife. It is a final gift to us that signifies our entire trip. Then on Sunday, my birthday, we attend church in Lucknow. Even though we are physically and emotionally spent, God meets us here. The worship leader encourages us to place our joys and victories at the foot of the cross, as even these belong to Him. God replenishes the bread in our hands and we are satiated. Over the past five weeks we have been broken open and offered as bread for other broken people and the distant memory of our painful past is shaped into hope for our future. “Praise the Lord… He heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds” (Psalm 147: 1, 3). Becoming bread for others brings unrivaled joy.

Then our thoughts turn towards home. With warm hearts, we are excited to reunite with our children and catch up with friends. Our faith has been strengthened and renewed and we feel the blessing of God on our lives and relationship. Imprinted on our souls are the courageous people we have known, sleeping with bread in their hands, holding what gives them life. Habakkuk 3:17-19 (NIV) expresses it perfectly:

Though the fig tree does not bud

and there are no grapes on the vines,

though the olive crop fails

and the fields produce no food,

though there are no sheep in the pen

and no cattle in the stalls,

yet I will rejoice in the Lord,

I will be joyful in God my Savior.

The Sovereign Lord is my strength;

he makes my feet like the feet of a deer,

he enables me to tread on the heights.

A Prayer…

David’s prayer of gratitude to God (Psalm 18:16-19, TPT):

[You] then reached down from heaven, all the way from the sky to the sea.

[You] reached down into my darkness to rescue me!

[You] took me out of my calamity and chaos and drew me to [Yourself],

taking me from the depths of my despair!

Even though I was helpless in the hands of my hateful, strong enemy, [You] were good to deliver me.

When I was at my weakest, my enemies attacked— but [You] Lord held on to me.

[Your] love broke open the way and [You] brought me into a beautiful broad place.

[You] rescued me—because [Your] delight is in me! [Parenthesis mine].

About the author: Dr. Paula Davis is a clinical counsellor, supervisor and educator specialising in psychological trauma. She has worked in higher education over many years as senior lecturer in counselling. Along with her husband she designs and delivers programs for war-traumatised couples and marriage enrichment/education workshops in Australia, Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Europe.

References

Ayano, G. (2016). Common neurotransmitters: Criteria for neurotransmitters, key locations, classifications and functions. Advances in Psychology and Neuroscience, 1(1), 1-5. doi: 10.11648/j.apn.20160101.11

Becker, R. (2006). The domain of perfect affection (1st ed.). USA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Linn, D., Linn, S. F., & Linn, M. (1995). Sleeping with bread: Holding what gives you life. USA: Paulist Press.

Milton, J. (2013). Paradise lost: book 1. eNotes, 14 June 2013, Retrieved from https://www.enotes.com/homework-help/analysis-statement-mind-its-own-place-itself-can-439906.

Rilke, R. M. (2020). Quotes. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/95915-let-everything-happen-to-you-beauty-and-terror-just-keep

Shakespeare, W. (1996). Hamlet. In T. J. Spencer (Ed.), The new Penguin Shakespeare. London, England: Penguin Books.

Simpson, J. & Weiner, E. (Eds.). (1989). The English Oxford dictionary. UK: Clarendon House.

Stanley, J. P. (2005). Doubt: A parable. New York: Theatre Communications Group.

Welling, T. (n.d.). QuoteFancy. Retrieved from https://quotefancy.com/quote/1464001/Tom-Welling-I-have-so-much-chaos-in-my-life-it-s-become-normal-You-become-used-to-it-You

Wormald, B. H. G. (1993). Francis Bacon: History, politics and science, 1561 – 1626. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Yancey, P. (1999). Where is God when it hurts? USA: Zondervan.

Yancey, P. (2000). Reaching for the invisible God: What can we expect to find? USA: Zondervan.

0 Comments