“Unforgiveness is like drinking poison yourself and waiting for the other person to die.” ~Unknown

“I’ve had my moments of crisis, which have led me to study and argue with God, at times dramatically… no heart is as whole as a broken heart, and I would say that no faith is as solid as a wounded faith.” ~Ellie Wiesel

“To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.” ~ Lewis B. Smedes

“Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. Forgive as the Lord forgave you.” ~Colossians 3:1

A Story of Forgiving

The towering mountains remind me of my littleness in the grand scheme of things. The road stretches before us as we indulge in some much-needed rest and recreation after conducting trauma workshops for war-traumatised couples in Northern Uganda. The issue of forgiveness floats across my mind and I’m struggling with it. How on earth could these people to whom we have just ministered, especially the women, forgive those who had raped, pillaged, murdered and mutilated their bodies? I had asked them: “How do you get up each morning after what you have experienced? How do you forgive?” A brave woman stood with tear-stained eyes and declared, “How can we not? It will destroy us if we don’t.” These thoughts are turning over in my mind like tumbleweed rolling over and over in the desert wind. Without premeditation, I turn to Barry and exclaim, “I realise I haven’t forgiven you for some deep hurts that occurred in our early marriage and even though I want to forgive, I’m not there yet. I need to wrestle with God about it.”

We push on to enjoy a delightful break swanning around South Africa. Delightfully, we cage-dive with great white sharks in the Atlantic Ocean, gaze at whales through the floor to ceiling window of our beachside accommodation, boat through spectacular caves and enjoy the enthralling antics of wild animals on safari, knowing we will come to a place of peaceful forgiveness when we are ready.

Nine months later, I am sitting in a beautiful garden during a marriage retreat we are conducting. In my journal I begin to list the particulars of what I am forgiving. As I see the items on the page I am struck with the paucity of them compared to the hurt I have bestowed on my husband during our darkest days. The paper lies in pieces at my feet. Celebrating communion at the close of the retreat is the God-appointed time for me to ask his forgiveness.

We could never have known how the simple act of forgiving would free us both for levels of intimacy previously unknown. In 2012, our story was powerfully used of God to free a damaged, murderous, traumatised man, born into a war that endured for decades of his life. While conducting a retreat for people-helpers in northern Sri Lanka, Barry and I turn to each other and share our story of forgiving in front of the group of around thirty war-traumatised attendees. Representatives of opposing ethnic groups that have been enemies for close on 30 years sit across from each other. The tension is palpable.

Following our sharing, Robert invites everyone to write down who they need to forgive. The folded papers are placed in a carboard box on the concrete floor. A candle is given to a representative from each ethnic group and also to us, symbolising years of brutal colonial domination. Simultaneously, we each light the papers and watch as the flames burn our resistance. A woman’s sweet voice pierces our reflections as she begins to sing. Soon, other women from the dominant ethnic group join in, crossing the floor to embrace the women from the marginalised ethnic group. The men follow, reluctant at first, but then heartfelt. It is a goose-bump moment of the power of forgiveness that sears itself on our heart’s memory.

Afterwards, a young man approaches Barry. He desperately wants to share something powerful, but the language barrier prevents communication. Instead, he pushes an ornate pen into Barry’s pocket as a gift, a symbol of a heart broken open. Three months on, we receive a translated copy of his letter written to Robert (used with permission):

I am an undergraduate of the Jaffna University [located in the far north of Sri Lanka where the hostilities began] reading for a Medical degree. I am a victim of the 30 long years of ethnic conflict and the bloody war that took the lives of my family members and often had to undergo many difficulties that many of you wouldn’t even imagine in your wildest dreams. This created hatred on Sinhalese [opposing ethnic group] as I thought they were solely responsible for this entire conflict. This wound (hatred) in me was eager to take revenge from Sinhalese and I have been looking for opportunities to kill Sinhalese.

I came with such a mind frame to this camp [the trauma workshop we conducted] and by the final day with lots of meaningful discussions and understanding the importance of forgiving and being forgiven I was finally able to forgive Sinhalese. That gave a great freedom and I was able to release such a pain in my mind and now I feel as if I have released a weight of a mountain that I have been carrying with me and suffering for many years. I am grateful for the teachers for the guidance given to me through this camp to be a free man who can love God’s greatest creation ‘humans’ regardless of nationality or ethnicity and to live in harmony for a peaceful world

Our hearts leap for, “from his fullness we have received grace upon grace” (John 1:17).

Forgiving Myself

Much later I come with a heavy heart to a woman’s conference. Forgiving myself is the hardest journey. Guilt and shame over past failures have infected my spirit and the contagion has spread to those I love. It remains an unresolvable dilemma – on the one hand, I could not have done anything different with what I had been given. On the other hand, I have irrevocably damaged my children through my earlier struggles with post-natal, suicidal depression. My little, innocent ones felt abandoned and my attachment to guilt and shame is tenacious. Watching them struggle with life, relationships and adult responsibilities crushes my spirit. My failure, fuelled by self-condemnation, lurks beneath the surface to accuse me. The past, shrouded in remorse and regret, cloaks my heavy heart in shame. My mother’s message has come true: I am the “Ruiner” of relationships. My self-judgment is brutal. What I fear most, I need to face, because I am punishing myself and creating my own misery. Just as I have been hurt in the past, I hurt myself in the present, perpetuating my suffering. The mercies of God do not penetrate. I cannot hear another voice.

Except I do! Jesus comes for my heart. The realisation dawns that the accusing voices I hear in my head are from the enemy. I have believed his lies about who I am and now I accuse myself. I am judge and jury of my fate and the verdict is the death sentence. Yet, God’s steadfast love and mercy pursue me and I am captured by eyes that see; eyes filled with profound love. His voice breaks through the condemnation, declaring, “Ruiner is not how I see you.” I am humbled enough to step down off the judge’s seat, as God pronounces, “No condemnation.”

I plead God’s forgiveness for believing Satan’s lie and for allowing it to define me. God whispers in my ear, “You are my healer, my restorer, my life-giver. Do you notice they are the opposite names to those your mother gave you?” My heart leaps with joy as I allow my new names to wash over me. And I hear Him whisper, “I am your true Father and you are mine. I am never going to abandon you.”

Boldly, I ask for more grace, for confirmation of his healing to come within the hour. As the morning’s session ends, my daughter asks to go into town for coffee. We sit in the warmth of the sun, our hands wrapped around warm coffee cups; the fragrance of God lingering. He has come for her heart too. We share our intimate God-revelations. I expose “Ruiner” to my daughter and the shame of it, expecting her to reinforce the image. I tell her my new names. Her eyes look deeply into mine as she offers grace, “Don’t you know how much life you give to me?” I shrink away – an instinctive, habitual response, except that for the first time I notice it and am shocked. I declare to God that from now on I choose to live out of the names He has spoken and sung over me. The warmth of His love envelops my healing heart. I forgive myself.

Forgiving God

You might be saying, “How can you suggest we need to forgive God – He does not require forgiving!” How often have we heard, “God will never let us down if we trust Him.” But how many of us question why God allows us to suffer? Take Emma, for example. She has been coming to counselling for three years. A nasty incident at work triggered a subterranean reaction, a breakdown of sorts in her meticulously fortified walls. Emma was sexually abused by family members from her preverbal days. Infants lack the emotional resources to deal with such ravaging destruction of identity, therefore, she was forced to split her emerging sense of self into various disconnected personalities in order to survive. Her “going-on-with-life”personality was hidden from her lonely, angry, aggressive and devastated parts, each with their own names. She found a safe place to let her shameful secret be known. How does she forgive God for allowing an innocent child to endure such brutality; the years of struggle and fighting for freedom to live?

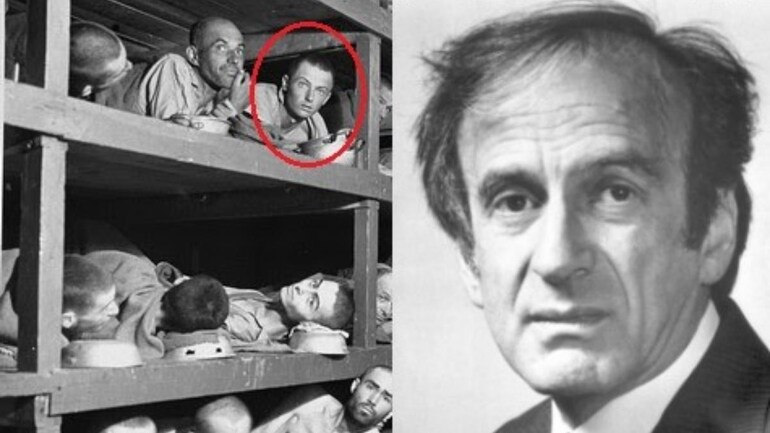

Since the Fall, the world is full of suffering, injustice, oppression and evil. Judaism and Christianity have traditionally taught that God’s nature is all-knowing, all-powerful and all-good. How do we reconcile this with the existence of evil and suffering in the world? Ellie Weisel (1982), a Hungarian-born Holocaust survivor, wrote Night, a composition based on his experiences as a prisoner in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Buna, and Buchenwald. Through his writings, Weisel is forced to re-evaluate God based on the atrocities he witnessed. The fact that God could watch the horrors that were being committed and not intervene was deeply disturbing to him. Robert Brown (1983, p. 142) writes of Wiesel, “Contrary to much popular interpretation, Wiesel’s indictment of God does not constitute a denial of God…if only one could deny and have it over and done with…at least the ground rules would be clear…” Rather than cast God aside, Weisel wrestled with the problem of how a loving God could countenance evil and suffering.

Source: holocaust__1___1_.jpeg

Leading up to the Holocaust, Weisel believed in the goodness of God. He writes, “Our [Jews] optimism remained unshakable. It was simply a question of holding out for a few days…Once again the God of Abraham would save his people, as always, at the last moment, when all seemed lost” (1968, p. 25). Weisel and his Jewish companions still had faith that God had a greater purpose in mind. However, as the subsequent horrors began to penetrate their previously indomitable theology, the apparent meaningless of suffering caused Pinhas, Weisel’s friend, to declare from the depths of the concentration camp:

Until now, I’ve accepted everything, without bitterness, without reservation. I have told myself: “God knows what he is doing.” I have submitted to his will. Now I have had enough, I have reached my limit. If he knows what he is doing, then it is serious; and it is not any less serious if he does not. Therefore, I have decided to tell him, “It is enough” (Weisel, 1968, p. 34).

In the face of such overwhelming evidence, Weisel agreed. He writes, “How could I argue with him? I was going through the same crisis. Every day I was moving a little further away from the God of my childhood. He has become a stranger to me; sometimes, I even thought he was my enemy” (p. 34). Eventually, Weisel concludes that his relationship with God cannot based on answers to his vexing questions. He laments:

Answers: I say there are none…What the answers have in common is that they bear no relation to the questions. I cannot believe that an entire generation of fathers and sons could vanish into the abyss without creating, by their very disappearance, mystery which exceeds and overwhelms us. I still do not understand what happened, or how, or why. All the words in all the mouths of the philosophers and psychologists are not worth the silent tears of that child and his mother, who live their own death twice.

Weisel’s faith was shattered during his experiences of abject torment. Yet he cannot reject his faith. In a sense, he has to forgive God for not being the God of his expectations. Speaking of Jesus, Nieuwhof (2018, p. 25) argues, “He stared hate in the face and met it with love.”

Unlike Weisel, Rubenstein, a contributor to the debate around Holocaust theology, responded by denying both the existence of the God of Judaism and God’s Covenant with the Jewish people. His publication, After Auschwitz, in 1966, coincided with the “death of God” movement in America. Rubenstein writes:

How can Jews believe in an omnipotent, beneficent God after Auschwitz? Traditional Jewish theology maintains that God is the ultimate, omnipotent actor in historical drama. It has interpreted every major catastrophe in Jewish history as God’s punishment of a sinful Israel. I fail to see how this position can be maintained without regarding Hitler and the SS as instruments of God’s will. The agony of European Jewry cannot be likened to the testing of Job. To see any purpose in the death camps, the traditional believer is forced to regard the most demonic, anti-human explosion of all history as a meaningful expression of God’s purposes. This idea is simply too obscene for me to accept… no religious community can endure so hideous a wounding without undergoing vast inner disorders (p.153).

Other Jews found what he wrote painful. However, for Rubenstein, the Holocaust represented a “challenge encapsulated in one seemingly simple question: How can Jews believe in an omnipotent and beneficent God after the tragedy of the destruction of European Jewry?” (Krawcowicz, 2015, p.29). His argument was, “If God is the ultimate agent in history, he must have been in some way involved in the slaughter of the Jews. The Holocaust, then, was part of a divine plan” (p.29). Obviously, the horrors of the Holocaust rocked the Jewish faith to its very core and generated a seismic shift in the Jewish peoples’ previously accepted faith in the goodness of God.

So, is God Good?

The enemy succeeds in imposing an effective conundrum called, “The Problem of Evil and Suffering” that causes us to be distracted from rich relationship with God. According to Joe Rigney (2012):

This is what the Incarnation is all about: the Author of the story becoming not just a character, but a human character. In this narrative, God is the storyteller and the main character. He is the Bard and the hero. He authors the fairy tale and then comes to kill the dragon and get the girl.

The Incarnation is God’s definitive answer to the emotional problem of evil. The living God is not a detached observer or absentee landlord. He does not stand aloof from the suffering and pain and evil that forms the central tension of his epic. The God who is born is also the God who bleeds, the God who dies, the God who identifies with our sorrows by becoming the Man of Sorrows, acquainted with grief. God comes down, in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, and draws to Himself all of the sin and the shame, the rebellion and the hate, the sickness and the death, and swallows it whole. And He swallows it by letting it swallow him. The Dragon is crushed in the crushing of the Prince of Peace. The triumphant hour of darkness and evil occurs on the day we know as Good Friday. God is indeed good! So, if God has done nothing wrong other than be who He is, why do we need to forgive Him?

First, we tend to blame God for the suffering that happens to us. It seems unfair to us that, “He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous” (Matthew 5:45). Bad things happen to others, not to us. Why do some parents of neglected, abused children grow up flourishing in life, while other children from loving, nourishing homes break out and break their parents’ hearts? Why do some Pastors with questionable theology thrive and some who have been faithful for years see no change? Life is unfair and this troubles us.

Second, we misunderstand God with our limited perception of what He is up to. We feel outraged when He does not live up to our hopes and expectations of Him. When God lets hurtful things happen, we carry the emotional weight of our disappointment and resentment and our hope plummets. At best, we live with the ache of disillusioned longings. The only path to freedom is to forgive God for being who we demand him to be in our lives. Otherwise, we live in a kind of hell of our own making, never experiencing the comfort or touch of God on our lives. God does not need our forgiveness – He has done nothing wrong. Forgiving God is for us. The prisoner set free is us.

Closing Thoughts…

Looking back on my journey of forgiving (and one often only sees clearly when looking back) I notice that forgiving my husband brought about a seismic shift in me that was powerful and pervasive, its tentacles still invading all my relationships. My heart, long bound, has been released to genuinely move towards loving well. Reaching for each other during stressful times along with being there for each other has been problematic in our marriage. For years we seemed unable to cross the ocean between us to genuinely meet and be present to each other in crisis situations. Yet, something profound changed with forgiving. We are softer, more tender, more willing to move into the hard places inside each other with compassion and empathy. I believe it is called intimacy! It continues to surprise us.

Looking back, I also notice how forgiving myself for harming those I love and forgiving God for not being the God of my expectations have also precipitated seismic inner shifts. Forgiving myself has set me free from the prison of mercilessness I am prone to inflict on myself and forgiving God has released a spirit of gratitude and worship in me.

Declaration…

I declare that God is slow to anger and full of compassion for me, His child. He forgives me as I humbly ask and trust in His Son, as Saviour and Lord of my life. I declare forgiveness over myself for the hurt I have caused to those close to me. I declare I will no longer live in condemnation, as I am in Christ Jesus. I also let go of my expectations and demands of who I require God to be in my life and in the world. I declare release and freedom over myself.

Prayer…

“Now to the one who is able to keep you from falling, and to make you stand without blemish in the presence of glory with rejoicing, to the only God our Savior, through Jesus Christ our Lord, be glory, majesty, power, and authority, before all time and now and forever. Amen.” (Jude 24-25).

Reflect…

What names were thrust on you as a young child?

What is God calling you to forgive yourself for right now?

What is God calling you to forgive Him for right now?

Ask God for His love to forgive — the same love that has forgiven you.

How do you feel now with God’s forgiveness working in and through you to forgive yourself?

Write or draw that feeling.

About the author: Dr. Paula Davis is a clinical counsellor, supervisor and educator specialising in psychological trauma. She has worked in higher education over many years as senior lecturer in counselling. Along with her husband she designs and delivers marriage enrichment/education programs in Australia, Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Europe.

References

Brown, R. M. (1983). Elie Wiesel: Messenger to all humanity (Rev. Ed.). USA: University of Notre Dame Press.

Rigney, J. (2012). Confronting the problem(s) of evil: Biblical, philosophical, and emotional reflections on a perpetual question. desiringGod. Retrieved from https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/confronting-the-problems-of-evil

Weisel, E. (1982). Night. New York: Bantam Books

0 Comments