“God is a redeemer, and His redemptive nature extends into the deep caverns of our regrets and failures. When we bring our failures and regrets into the light, we find God’s redemptive love brings something beautiful out of the ashes.” ~ Lisa Bevere (2018)

“When the morning’s freshness has been replaced by the weariness of mid-day, when the leg muscles quiver under the strain, the climb seems endless, and, suddenly, nothing will go quite as you wish – it is then that you must not hesitate.” ~Dag Hammarskjolfd, Markings

“Sometimes,” said the horse. “Sometimes what?” asked the boy. “Sometimes just getting up and carrying on is brave and magnificent.” ~Mackesy, The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse.

On a Tuesday in 2012 I had a meltdown. I know enough to realise I am experiencing vicarious trauma, absorbing the suffering and pain of a war-traumatised people I have come to love. But I know it is more than this – it is a spiritual questioning. I am lamenting and searching the heart of God for answers to the world’s suffering, answers that I can live with, work within and yet still vibrate with joy. It is not the first time I have visited this inner space and I am sure it will not be the last. Maybe that is why I am drawn to this type of ministry, because it lures me into the ring to wrestle with deep spiritual uncertainties. Needless to say, there is always a parallel process. My suffering, although not comparable to that of the war-traumatised, nevertheless contains a response to trauma, compelling me to continually seek the face of God for core healing that only He can bestow.

It is a few days before Christmas. My Australian neighbour calls at my door to return a bowl from our street party last night that I did not attend. My excuse was sickness, but it was heart sickness I was suffering. She tells me I was missed and I burst into tears. Surprised but kind, she assures me I have a community in my street that can surround me, this gutted, bleeding woman bent low. How do I live with this throbbing heartache? I feel myself closing up and I don’t want to, because it means I will close off to grace as well.

On Christmas Eve I drag my exhausted body and spirit from my bed to a glorious morning, wondering how I can ever again wake up to joy, beauty and grace, when my brothers and sisters wake up to the ugly mess of war and death, aching grief, imploding relationships, crushed dreams and numbness that empties the soul. I know from experience that when grief is deepest no words suffice and no comfort upholds. Matthew 2:18 says it well, “A voice is heard in Ramah, weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more.”

Yet, I deeply believe that, “Pain can be endured and defeated only if it is embraced. Denied or feared it grows” (Koontz, cited in Singer, 2018, p. 365). I tell this to others with the passion of a zealot, but what about me? How can I live with joy in this toxic world when my heart and eyes see the unendurable, the unbearable and the excruciating? How do I not close down and deny? How do I embrace this gnawing angst? How do I take rest and refreshment in the presence of my God? How do I hold all this pain and loss, this aching sadness, and still live with a large heart? How do my Sri Lankan friends rise to hope on Christmas morning when their “most painful state of being is remembering the future, particularly one you can never have” (Kierkegaard, n.d.).

I pick up my Bible seeking comfort and refuge. I read how I can take comfort in the loving heart of God and am struck that God’s heart aches for these precious people as well. He clearly tells me that my heart is breaking because it is deeply touched by the things that break His, that my broken heart resonates with His. He tells me He wants to be my strength in times of weakness and comforter in times of sorrow. He tells me he created me (and them) to live in freedom, even when the heart breaks and the rawness aches. He tells me He wants to heal, make whole and restore.

Tears spill out staining the page and my heart breaks open afresh. I read how falling tears are caught and captured in God’s bottle. I know He knows me, “whose heart is torn by secret sufferings, but whose lips are so strangely formed that when the sighs and the cries escape them, they sound like beautiful music…” (Kierkegaard, cited in Hollis, 2000, p. 37). I purposefully slow down to make beautiful music in my heart to God, to sit with the pain. The only Christmas present I really need to wrap today is my heart around His, to rest in Him. I fall on my knees and tell Him I do not understand the world’s suffering, I’ll never understand and ask Him to, “Restore to me the joy of your salvation and grant me a willing spirit, to sustain me” (Psalm 51:12). Rest is what I need, the kind of God-rest that is deep and sustaining found in Matthew 11:28-30 (MSG):

Are you tired? Worn out? Burned out on religion? Come to me. Get away with me and you’ll recover your life. I’ll show you how to take a real rest. Walk with me and work with me—watch how I do it. Learn the unforced rhythms of grace. I won’t lay anything heavy or ill-fitting on you. Keep company with me and you’ll learn to live freely and lightly.

God reminds me this Christmas that Jesus came into this broken world of evil and suffering and took our wounds on Himself. He came, God came, tasting death, sorrow and evil. He became “God with us”, the God who dwells with my Sri Lankan friends this Christmas in their agony, their weeping, their loneliness, the God who is within them, the God who gives them rest. I get up from my writing, holding Him in the depths of my heart knowing that He holds them and I am moved to pray this lament:

God of my life, as I enter into another beginning, a new year, give me a large heart and open hands. May I live gently, knowing that the path to healing and joy is not what I might expect; that it involves an awakening and a grief. Forgive me for numbing my soul, for trying to dull the unrelenting pain of loss that affords me the illusion of control; for exercising strategies intended to protect me, but really causing harm to those I love and inflicting greater self-harm. Forgive me for forfeiting myself and damaging others. May I live into the future believing I am loved by Everlasting Love that frees me to genuinely love myself and others.

May my dear, shattered Sri Lankan friends choose to come alive in God this Christmas. Even though it costs them dearly, may they choose the courageous path. May they know that healing for their deepest wounds begins by first acknowledging them. Show them that many of the strongest and weakest of us are indeed crippled heroes. Make my life a gift to others. May I become the blessing that deeply blesses. Help me and them to choose the narrow path always, the path of life, the path of genuine dependence on the “God who sees me…” and the path that leads to a life of integrity.

Learning to Lament

Our society often pressures us to hide our grief but lament allows us to fully express our grief, even to accuse God, while still trusting in Him. An example is found in Psalm 13:1 where David pleads, “How much longer will you forget me, Lord? Forever?” Yet in verses 5 and 6 he declares, “I rely on your constant love; I will be glad, because you will rescue me. I will sing to you, O Lord, because you have been good to me.” How can David believe and declare both of these seemingly contradictory statements simultaneously?

According to 2 Samuel 1:17-27, “David took up this lament concerning Saul and his son Jonathan, and ordered that the men of Judah be taught this lament…” No one teaches us to cry. David says we must learn how to lament, how to Biblically cry, how to grieve the losses that run through all of our lives. In other words, we can and must learn to lament in order to heal. The Message translation renders 2 Samuel 1:18 as, “David sang this lament…and gave orders that everyone in Judah learn it by heart.” What transforms our cries, our complaints and our anger into lamentation? David does not write grumbling cries, he writes lamentations and poetry. Is this what we, too, are called to do with our pain? Learning to lament teaches the heart to see God’s face everywhere, especially in our pain.

Perhaps God gave us lament for emotional containment. Flooding, intrusive thoughts, flashbacks and out of control feelings all maintain a crisis. Emotional containment takes a person’s experience and places it in a safe place until it can be dealt with later. Containment shifts and recalibrates the amygdala in the brain to begin the process of emotion regulation. Emotional containment is not resolution, but a short-term strategy that enables the processing of distressing and traumatic material in manageable parts (Williams & Poijula, 2002). It assists a person to function each day without being emotionally overwhelmed. Someone that has experienced overwhelming pain and trauma experiences intense feelings that can seem uncontrollable. Emotional containment provides a way to tolerate the feelings and helps the person to not only choose when they are ready to work on the memories, but to be more present in daily life.

Lament as Emotional Containment

Could God have provided lament as a way to contain overwhelming grief and emotions? Being strong enough to cry takes the rawest courage. Have you ever sung the hymn, Great is Thy Faithfulness? It comes from the familiar and well-known Bible passage in Lamentations 3:22-24, but we seldom reflect on its context. It reads, “Yet this I call to mind and therefore I have hope: because of the LORD’s great love we are not consumed, for his compassions never fail. They are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.” Lamentations was written around the time of the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylonian invaders in 586 BC. Jeremiah had devoted his life to calling his people back from headlong plunge toward disaster, but his people failed to heed his warning. Now he is surrounded by smoking rubble and dead, wounded, starving people.

Moreover, King Nebuchadnezzar’s soldiers laid siege to the children of Israel’s precious temple, the symbol of God’s presence and protection. God’s people are marched off to a foreign land where they wail, “How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?” (Psalm 137:4 ESV). What might Jeremiah have felt? Jeremiah struggles. He doubts. Yet, he expresses his struggles and doubts to God in a lament (Lamentations 3: 1-21, MSG) that reads:

God Locked Me Up in Deep Darkness

1-3 I’m the man who has seen trouble,

trouble coming from the lash of God’s anger.

He took me by the hand and walked me

into pitch-black darkness.

Yes, he’s given me the back of his hand

over and over and over again.

4-6 He turned me into a scarecrow

of skin and bones, then broke the bones.

He hemmed me in, ganged up on me,

poured on the trouble and hard times.

He locked me up in deep darkness,

like a corpse nailed inside a coffin.

7-9 He shuts me in so I’ll never get out,

manacles my hands, shackles my feet.

Even when I cry out and plead for help,

he locks up my prayers and throws away the key.

He sets up blockades with quarried limestone.

He’s got me cornered.

10-12 He’s a prowling bear tracking me down,

a lion in hiding ready to pounce.

He knocked me from the path and ripped me to pieces.

When he finished, there was nothing left of me.

He took out his bow and arrows

and used me for target practice.

13-15 He shot me in the stomach

with arrows from his quiver.

Everyone took me for a joke,

made me the butt of their mocking ballads.

He forced rotten, stinking food down my throat,

bloated me with vile drinks.

16-18 He ground my face into the gravel.

He pounded me into the mud.

I gave up on life altogether.

I’ve forgotten what the good life is like.

I said to myself, “This is it. I’m finished.

God is a lost cause.”

It’s a Good Thing to Hope for Help from God

19-21 I’ll never forget the trouble, the utter lostness,

the taste of ashes, the poison I’ve swallowed.

I remember it all—oh, how well I remember—

the feeling of hitting the bottom.

These are powerful and even shocking words. Ever been there? Could Jeremiah be just as spiritually alive in verses 1-20 as in 21-24?

What is a Lament?

Lament is a Biblical response to distress. Lament consists of poems or songs expressing deepest heart emotions, such as distress, despair, joy or ecstasy. The intensity of emotion is captured and expressed in the language of vulnerability, pain and questioning that often includes doubt and protesting (Seerveld, 2005). Lament be individual or community expressions of traumatic pain that connects people in their brokenness and validates their distress, a communal cry to God for compassion.

Historically, lament was voiced and read aloud, usually by the elders of the community, not necessarily to voice the details of the event, but the emotions. Sixty-seven of the Psalms in the Bible are considered laments and constitute more than any other type of Psalm. The Psalms offer a prototype for lament. As you read through the list below, tick those that apply to you:

-

- Dried out and shrivelled (Psalm 22)

- Weakened (Psalm 61:3; 102:1; 77:4; 142:4 143:4)

- Oppressed (Psalm 103:6)

- Undeserved suffering (Psalm 69:5-6)

- Tortured, desperate, incapacitated (Psalm 72:14)

- Anguish, languishing (Psalm 6:3)

- Spent (Psalm 31:1; 39:11; 69:4; 102:4; 71:9; 143:7)

- Tired (Psalm 6:7; 69:4)

- Losing strength (Psalm 38:11; 40:13)

- Abused and powerless (Psalm 38:12)

- Abandoned (Psalm 142:4)

- Unable to find words (Psalm 73:16-17)

- Groaning with guttural anguish (Psalm 6:7; 31:11; 38:10; 102:6)

- Bones are crushed and the heart shattered (Psalm 34:18; 51:8, 17; 147:3)

Photo by Tessa Rampersad on Unsplash

In lament, these complaints are poured out to God in an attempt to persuade Him to act on the sufferer’s behalf, while simultaneously declaring ultimate trust in Him. An example of a declaration of trust is found in Psalm 62:8 (MSG):

My help and glory are in God

—granite-strength and safe-harbor-God—

So trust him absolutely, people;

lay your lives on the line for him.

God is a safe place to be.

Lament allows the hard questions to sit unanswered: the “why” and “where is God” questions. Lament allows paradox; that is, we know that all agony is answered and settled in Christ, but those who are living through real life traumatic situations are experiencing overwhelming distress. Lament is not for those who require absolutes and concrete answers. If Iheld up a black sheet of carboard and asked you what you see, you might reply that it looks solid, strong, dominant, without room for colour. If I then held up a white sheet of cardboard, you might reply that it has no colour, a nothingness or that it seems washed out. If I held up a grey sheet of cardboard, you might say that it is not distinct, that it consists of both black and grey. The grey cardboard is like lament, it allows both sides of the paradox to sit unresolved.

What is it like to sit with unresolved pain and trauma? What is it like to not have concrete answers? Rainer Maria Rilke wisely wrote:

Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart. Try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books written in a foreign language. Do not now look for the answers. They cannot now be given to you because you could not live them. It is a question of experiencing everything. At present you need to live the question. Perhaps you will gradually, without even noticing it, find yourself experiencing the answer, some distant day.

What Does a Lament Contain?

Laments can be divided into parts According to Seerveld (2005), lament can contain up to seven parts. These are:

1. An address to God; for example, “O God…”

2. An appraisal of God’s faithfulness in the past

3. A complaint

4. A claim of innocence or a confession of sin

5. A plea for help

6. God’s response (often not stated)

7. A pledge to praise or statement of trust in God

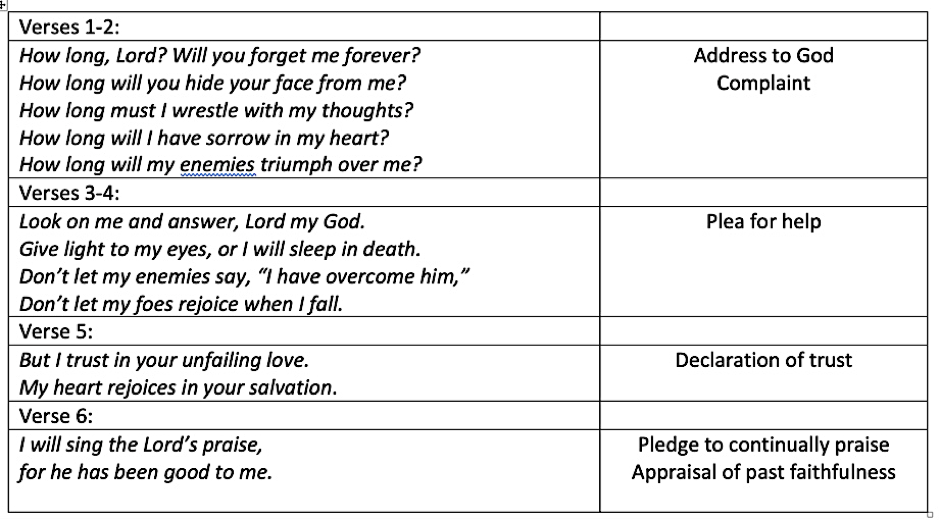

Psalm 13 contains some of these elements.

On the other hand, Mark Vroegop in Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy, streamlines lament into four steps:

-

- Turn

- Complain

- Ask

- Trust

What are the Benefits of Lament?

Public or community lamenting can break an individual’s sense of aloneness and alienation that spirals from suffering, trauma or grief. A song or story (especially involving movement) offers a measure of reassurance and control – the terror is over, we are in a state of transition (Lee & Mandolfo, 2008). Lament can offer a measure of psychological closure. This can be difficult, as presenting a traumatic story is to remember the horror of what one most wants to forget. Yet, for my dear Sri Lankan friends, once told, these storied memories allow the group to share grief, identify with and validate each other’s stories and songs of past sorrow (Lee & Mandolfo, 2008). This is similar to the witness’s role in a testimony – the community witnesses each other’s acts of mourning and, subsequently, a new identity is formed as social bonds of witnessed suffering are affirmed (Miller, 1994).

Moreover, traumatic memory can block or erase other forms of memory. When the memories of terror and violence are repressed, morphing into posttraumatic stress disorder, the traumatic grief is indirectly transferred to next generation. As we watched children of traumatised parents, we feared the ongoing generational impact. However, the song of lament, once it becomes well-known, can interrupt, replace, or alter traumatic images, making them less invasive and less likely to make one numb or “dead” to life (Lee & Mandolfo, 2008), a characteristic of traumatised people that deeply affects their relationships. Also, if the dead and traumatised are shrouded in silence, they are not collectively mourned. Thus, a public expression of trauma invokes a collective memory through which fragments of personal memory can be assembled, reconstructed, shared and validated by the group (Lee & Mandolfo, 2008).

How Can We Give Voice to Pain, Anger and Distress?

Trauma, grief and loss mostly silences the capacity to speak about emotional pain. Judith Herman (2015) proposes that traumatic emotional pain closes down the sense of self and silences one’s voice. To have a voice means that the self is re-emerging, gaining an identity and realising the truth of one’s history. The voices in Lamentations express acts of survival, resistance to death and resilience. The voices do not know what caused the tragedy or how to respond to it, but survivors rise, each in turn, to tell of their particular pain and to demand God’s attention. Yet, the voice of God for which all voices yearn is “missing” from the book. It is suggested that perhaps God’s silence honours and reverences the human voices of suffering by not closing them down prematurely (Brueggemann, 1995; 1997).

There is pressure in moving too quickly to hope. We would like Lamentations to end with words of hope where God resolves the pain and brings hope to despair. But the poems in Lamentations grow shorter, less energetic and more diminished towards the end of the book, as if in the aftermath of tragedy, hope cannot be sustained. What if this is the path to healing, even through we do not readily recognise it? For in Lamentations, hope soars, then fades, soars then fades. It barely survives, perhaps because God appears as a perpetrator throughout the book. The poetry rages in protest against God for perceived unjust, excessive punishment and failure to protect the innocent. In the final chapters, hope almost disappears entirely, yet pleads for God to see and intervene into the community’s plight (4:16; 5:1-20). Other voices struggle with who is to blame, but in the end of the book, the cost of devastation is all-consuming and hope is diminished.

The content of the book of Lamentations has been called “a theology of witness” (O’Connor, 2002) – the capacity to absorb and notice the enormity of suffering for what it is, in all its horror, immensity and overwhelming power and offer it back to the sufferers. In this way, the book offers comfort, representing a major step toward healing because, “The poetry recognizes the sufferer’s true condition and mirrors it back to them. This gives language to speak about their shared suffering…and enables them to take steps out of the isolation that intense suffering produces” (Lee & Mandolfo, 2008, p. 31).

Often, we find it difficult to move beyond the seeming injustice of a situation. Interestingly, Lamentations is also about politics and power. God is dominant in power and Israel is subordinate. The sufferer wants to redress this balance, allowing the community to complain openly and to be heard and their voices valued. Lamentations 5:21 represents Israel’s public complaint, “Restore us to yourself, O LORD, that we may return; renew our days as of old.” Verse 22 represents the hidden complaint of vexation and anger that cannot be publicly expressed for fear of punishment: “…unless you have utterly rejected us and are angry with us beyond measure.” According to Lee and Mandolfo (2008, p. 69):

For most bondsman through history, whether untouchables, slaves, serfs, captives, minorities held in contempt, the trick to survival…has been to swallow one’s bile, choke back one’s rage, and conquer the impulse to physical violence. It is the systematic frustration of reciprocal action in relations of domination which, I believe, helps us understand much of the content of the hidden transcript.

Lament gives voice to injustice and oppression.

Lamentations closes with a community lament that suggests that after a time of traumatic turmoil, those who remained in the city were utterly traumatised and exhausted, attempting to live and survive the aftermath of war. Lamentations 5:20-22 (RSV) reads, “Why do you always forget us? Why do you forsake us so long? Restore us to yourself, O LORD, that we may return; renew our days as of old unless you have utterly rejected us and are angry with us beyond measure.” The lament emerged from the heart of the community, infiltrating the deep emotions of suffering. The differing voices suggest that when one person was too emotional to continue, another would pick up the refrain. The lament contained communal grief in ways that offered mutual comfort. Thus, a stricken community that regularly voices lament is a community that acknowledges present pain and anticipates future transformation (Brueggemann, 1997). How might the introduction of lament benefit our church communities?

God Finally Speaks

When God finally speaks, about the “city woman” in Isaiah, He declares He sees her overwhelming suffering and loss. God attempts to comfort and restore her by using the image of a nursing mother to conjure God’s inability to forget Israel, His chosen people, expressed in Isaiah 49:14:

But Zion said, “The Lord has forsaken me,

the Lord has forgotten me.”

“Can a mother forget the baby at her breast

and have no compassion on the child she has borne?

Though she may forget,

I will not forget you!

See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands;

your walls are ever before me.”

Zion (God’s people) suggested that God had forsaken and forgotten her. Yet God assures her that He has a tender affection for her. Zion’s fears of being forsaken by God reflect on His character and He wants to clear himself. However, He is also deeply, tenderly concerned for his people; they are down, discouraged and negative thoughts go around in their heads. God says, “You think that I have forgotten you. Can a woman forget the infant at her breast?”

Perhaps God uses the metaphor of a nursing mother forgetting her infant because it is not a likely scenario. We tend to have a stereotypical image of a nursing mother whose compassion is aroused because her child, harmless and helpless, evokes it. A mother cannot be unconcerned, for it is her own child, a piece of herself and one with her. But it is also possible a mother may forget or even turn against her child. Perhaps she is so unhappy or depressed that she is not to be able to be there for her child or she may be so unnatural as a mother that she has no compassion “on the child of her womb.” God says that even though a mother may forget, “I will not forget you.” Imagine for a moment the tenderest mother you can think of towards her child. God’s compassions to you and me infinitely exceed them. We are His delight!

Further, God says, “I have engraved you on the palms of my hands.” Another translation says, “I have written your names on the backs of my hands.” When God sees the back of His hand engraved with my name, He remembers me in his heart and is mindful of my needs and my welfare. He thinks of me with love and delight. Write God’s name on the back of your hand and every time you see it today, remember His tender love for you. Henri Nouwen (1991) expressed:

You are my child. You are written in the palms of my hand. You are hidden in the shadow of my hand. I have molded you in the secret of the earth. I have knitted you together in your mother’s womb.

You belong to me. I am yours. You are mine. I have called you from eternity and you are the one who is held safe and embraced in love from eternity to eternity.

You belong to me. And I am holding you safe and I want you to know that whatever happens to you, I am always there. I was always there; I am always there; I will be there and hold you in my embrace.

You are mine. You are my child. You belong to my home. You belong to my intimate life and I will never let you go. I will be faithful to you.

Lament in Gulu

We arrive in the town of Gulu in Northern Uganda to the familiar red dust and sea of sad faces. I am gripped by a depth of sorrow that rips through my heart. I ache for these Acholi people whom I have come to love as family. They have suffered through twenty years of brutal violence and war. Arriving late we are summoned to the Diocesan Secretary’s home before we can refresh ourselves from the long trip. The ritual ceremony of hand washing before eating reminds me of Bible days when it was customary to wash the feet of guests. A water jug suspended over a basin is offered to each person in turn. The red dust clinging to our hands turns the water to the colour of wine. After the mandatory hospitality that is quite touching, we retreat to our hotel.

I stand on our balcony looking out over Gulu. I am instantly moved to compassion and the aching sorrow returns. Tears stream, carving rivulets in the African dust caked to my face. I recall Jesus high on a hill overlooking Jerusalem weeping for the city of Jerusalem for a people who were like sheep without a shepherd. I ask that the next few days might be a small step in the healing of these wounded, broken people. Later, we trawl the markets for drums and settle on a few purchases for the upcoming workshop.

I wake early, anxious about the first day of our gathering. A faded memory stirs in my awareness that the fan stopped at 3am and has not restarted. No electricity. I cannot make an early cup of tea with my water boiler. Deprived of small comforts I am restless and irritable. I try to pray and settle my rising apprehension. I know this spiritual battle well.

The concrete walls of our meeting room are painted the colour of African dust. Doorways without doors are positioned to catch a cross breeze. Old wooden benches afford participants aching backs but they will sit for three days without complaint. A religious service is underway, complete with robes and the whole shebang. I cannot enter just yet. There is something I must do. I walk around the perimeter if the building and pray protection over this meeting place, aware that eyes are puzzling over what this seemingly mad white woman is doing! When the procession of religious leaders leave the meeting place, participant eyes on high alert secretly dart while sizing up these “Musungus” waiting in the wings to engulf the meeting place for three days. Introductions and preliminaries are long and laborious and I intuitively know our intended program has just gone out the window as usual. We are now truly under the invitation and guidance of the Spirit of God. The ensuing drumming, singing and dancing lighten our spirits. I take in the scene. I recognise just one word repeated in the loud, uplifted voices – Jesu, Jesu, Jesu and my heart knows I’m home!

Barry begins with a devotion on the topic of woundedness. He calls me to the front and together we dialogue through interpreters about how we have wounded each other through the years. People immediately soften and we know we have given permission for vulnerability. The group is large so we divide it into seven smaller groups with one of our team facilitating each group. This gives each person a voice even though several of the women are suffering from traumatic speechlessness. Their trauma is written on their faces, the silent pain reflected in the black pools of their eyes. It breaks me.

We begin with a rationale for lament. We set the scene by explaining the concept of containment as a way of reducing distress so that one can function on a day-to-day basis. A pictorial distress ladder scaled from one to ten becomes an evaluative measure of participants’ distress. We explain how lament was traditionally an expression of intense emotion and questioning of God. At the end we ask where they are on the distress ladder and many reflect that they have risen to an eight or nine. We stop and ask what would be most helpful. The Ugandan way is to sing and dance and that is what they do. Then. we encourage each group to write, dance, drum or sing an individual lament to God expressing their pain. They honour us by performing their laments and we are deeply moved.

On the second morning, Barry’s devotion is on Esau’s pain. Together, we stand before the crowd and converse with each other about how we are moving though our woundedness. In groups, the Acholi people begin to share their wounds with each other. Acholi couples do not look into each other’s eyes, so I tell them that the eyes are the windows to the soul. Nervous laughter breaks out. I teach how trauma affects the couple relationship and how research reveals it is not so much what happens to you but into whose arms you can fall. The seeds are being planted. The first dawning of insight lights up their faces like stars in a dark night sky.

The final morning’s devotion centres on forgiveness. Again, we launch into a conversation around our journey of forgiveness. We weep and are genuinely vulnerable. Participants are touched. We see Miriam and Moses (not their real names) looking into each other’s eyes and smiling. Our hearts wobble and we weep for the umpteenth time. You see, Miriam was abducted by the rebels when she was ten years old and spent two years in the bush as a sex slave witnessing unspeakable atrocities. Moses rescued her and fell in love with her. Last year Miriam was unable to smile and the pain in her face broke our hearts. Last year she was there but not there and she became for us a symbol of a traumatised people. This year she smiles, a small act with large implications – she is healing. We speak with her through her husband (who speaks English) about how we thought she was the bravest woman we know. She smiles shyly and her eyes convey the gratitude of one who is beginning to experience her hunger for connection.

On our final afternoon, we speak of lamenting as a community, how trauma blocks and sometimes erases previous memories. So, we help them to remember their mourning rituals from before the war. It is now time to compose a community lament, helping them to come back to what they already know. Each group performs a lament on a different theme using song, dance, drumming and sometimes words. Our hearts are overwhelmed and break open.

I hate endings and this one is no different. One of the community leaders is called upon to offer us, the facilitators, some closing remarks. He looks at us and in a warm, soft voice that hold us captive he says, “On the other side of the world, these two heard the whisper of God and He sent angels to give us what He knew we needed.” We lose it on the “whisper of God”. Months of preparation with blood, sweat and tears are suddenly, in a moment, all worth it. In our right of reply we tell the Acholi people we love them and will be back as often as we can. We are reluctant to leave and will need to wrench ourselves away. There is so much to be done to make a difference in these broken lives. They have lamented and tomorrow we will weep and give these hurting people over to the care of God through the gift of our lament.

Reflect…

- What difficult and painful questions are you struggling with at present?

- How would you define trust?

- How could lament be an expression of your own suffering and that of others?

- What is your relationship with hope and trust?

- What would you like to say to God about hope and trust?

Closing Thoughts…

God gives us a pattern for lament in the Scriptures to enable us to express our profound pain and even question Him. He is not afraid of the intensity of our pain, but bids us voice it to Him, knowing that the peace and freedom we seek is available only through trust in Him.

A Declaration…

I declare that I will voice my grief to You, God, to counteract despair, defeat and hopelessness. I declare that Jesus conquered sorrow and death and because He lives, I will live. I declare that I will fight for hope until it fills my soul and lights the way to freedom.

A Prayer…

Saint Benedict exhorted, “Always we begin again.” Lord, we ask for the heart to begin again. Life brings such blinding things. Help us to trust in Your goodness and faithfulness, even when we cannot see it. Help us to use your pattern of lament to express the hidden struggles of the heart. Then, Lord, come for us. Heal us and restore our souls. In Jesus name, Amen.

About the author: Dr. Paula Davis is a clinical counsellor, supervisor and educator specialising in psychological trauma. She has worked in higher education over many years as senior lecturer in counselling. Along with her husband she designs and delivers marriage enrichment/education programs in Australia, Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Europe.

References

- Brueggemann, W. (1995). The Psalms & the life of faith. USA: Fortress Press.

- Brueggemann, W. (1997). Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, dispute, advocacy. USA: Fortress Press.

- Herman. J. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. USA: Ingram Publisher Services.

- Guinan, M. D. (2002). Biblical laments: Prayer Out of Pain, Franciscan School of Theology, Berkeley, California. Retrieved from http://www.americancatholic.org/Messenger/Mar2002/Feature2.asp

- Lee, N., & Mandolfo, C. (Eds.). (2008). Lamentations in ancient and contemporary cultural contexts. Atlanta, GO: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Mackesy, C. (2019). The boy, the mole, the fox and the horse. UK: Penguin Random House.

- Miller, P. D. (1994). They cried to the Lord: The form and theology of Biblical prayer. USA: Fortress Press.

- Nouwen, H. M. (1991). Our first love. Excerpt from a lecture given at Scarrit-Bennett Center. Faith Foundations. Retrieved from http://www.deeper-devotion.net/support-files/faithfoundations_identity_theme2wk1.eng_1-1.pdf

- O’Connor, K. M. (2002). Lamentations and the tears of the world. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

- Seerveld, C. (2005). Voicing God’s Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

- Vroegop, M. (2019). Dark clouds, deep mercy: Discovering the grace of lament. Ill, USA: Crossway.

- Williams, M. B., & Poijula, S. (2002). The PTSD workbook: Simple, effective techniques for overcoming traumatic stress symptoms. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

0 Comments