“When you get married, your spouse is a big truck driving right through your heart. Marriage brings out the worst in you. It doesn’t create your weaknesses (though you may blame your spouse for your blow-ups)—it reveals them.” ~Timothy Keller, The Meaning of Marriage

“He who angers you conquers you.” ~Elizabeth Kenny

“Fools give full vent to their rage, but the wise bring calm in the end.” ~Proverbs 29:11

How Can Anger Be Understood?

Photo by Noah Buscher on Unsplash

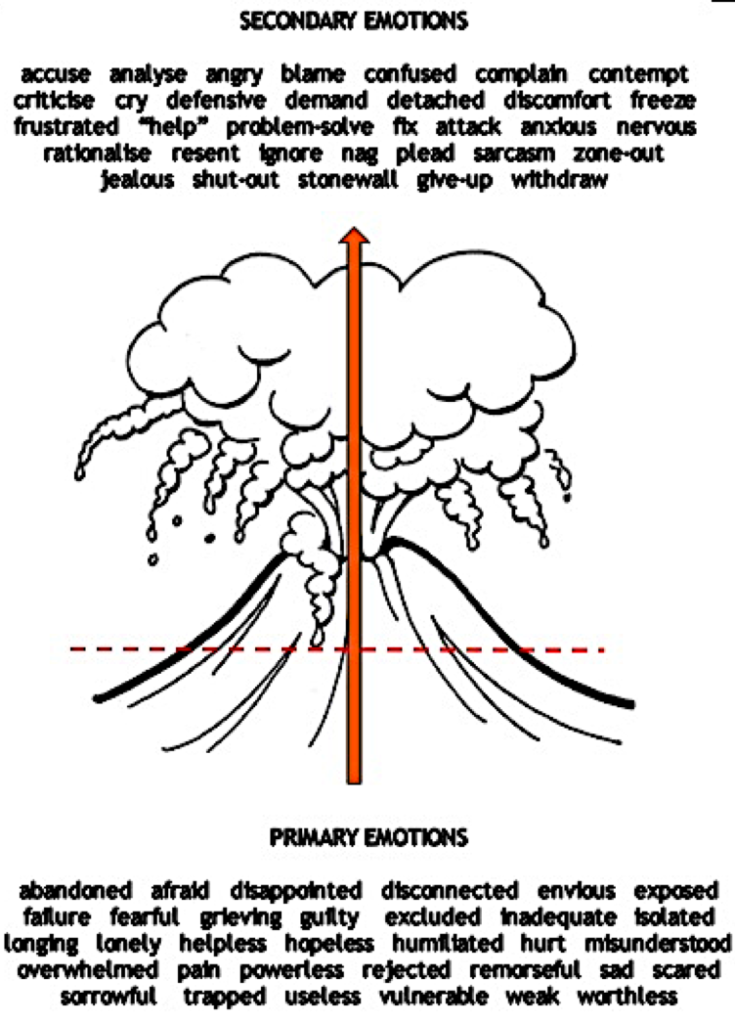

In the last blog, I mentioned the volcano metaphor (depicted below) and how it reveals anger as a disguise for more vulnerable emotions like hurt, fear, helplessness, abandonment, inadequacy, grief or shame. Anger empowers and protects us from being taken advantage of by another person. In fact, Jennifer Freyd (2002) claims that in the wake of a terrorist attack, hatred and rage may mask fear and grief. She believes that hate crimes may be responses to stress called flight‐or‐fight. When flight is not an option, identifying and hating an enemy may be the only way to survive; for example, angry shoppers in the USA chased a group of Middle-Eastern women and children from a store because they were assumed to be Muslim and terrorists.

Nevertheless, there is not a “one size fits all” way of understanding anger. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow articulated, “If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.” So, a good starting place to understand anger is the premise that chronic anger usually stems from deep pain and the fear of vulnerability. Therefore, in dealing with anger, the underlying primary feeling state beneath the volcano must be recognised and acknowledged. Anger will be explored here from two different perspectives – the drama triangle and anger that honours God.

A Victim Mentality

Some years ago, a bruising interchange with a family member, simultaneously generated in me a negative and positive response. As was my usual stance, I reacted by withdrawing and hiding from others and from my own life. I felt sorry for myself and nursed perpetual feelings of helplessness, negativity, guilt, shame and desolation. A victim mentality permeated my responses and my life. Constantly being at the mercy of the harmful actions of others (despite evidence to the contrary) was exhausting.

This is not uncommon in those who were raised in unhealthy emotional environments. Unlike a Martyr Complex, where a person seeks to suffer under the guise of love or duty, a Victim mentality dwells on their helpless fate while refusing to accept responsibility for their harmful behaviour. Of course, a Victim believes they have no power to change their circumstances! Victims thrive in relationships where the other is either a Rescuer or a Persecutor. All positions tend to fit angry people who respond to their helplessness by using different survival patterns in the drama Triangle.

The drama triangle

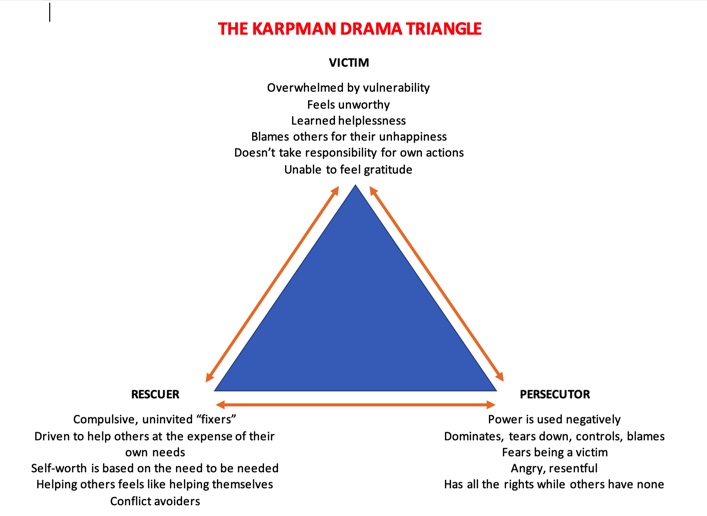

The drama triangle helps me to understand both passive and aggressive anger states. Someone once aptly wrote, “Maturity starts when drama ends.” The drama triangle is explained by Carmen Berry (2003) who suggests that we often learn as children to relate in one of three styles, now known as the Karpman Drama Triangle (cited in Johnson, 2018):

- Victim;

- Persecutor; and,

- Rescuer or “Messiah”.

The drama triangle is visually depicted below.

It is not unusual to swing between the three roles. Nevertheless, we tend to adopt one as our default and employ it as a defense against shame; for example, in my less than ideal childhood, I unconsciously assumed the role of Victim to protect my fragile self-esteem and manage the anxiety generated from people, situations and events. My parents failed to require me to assume age-appropriate responsibility for myself, so I grew into a resentful adult who blamed others when I did not receive the nurture and care I believed I deserved and should receive. The role I chose for self-protection as a child offers me a skewed sense of power and responsibility as an adult.

This is true for most people who were raised in abusive or manipulative homes. They become caught in a destructive drama triangle, taking either a Victim, Persecutor or Rescuer role (Berry, 2003). All three roles keep us stuck in a destructive cycle evidenced by behaviour at the top of the volcano and violate the boundaries of others. However, all three styles stem from deep pain and fear of vulnerability. Let me explain how each role works.

The Victim

My default role, chosen as a self-protective strategy, was playing the Victim. The victim believes, “I get to feel safe by not being responsible or accountable for my actions. I am entitled to sympathy from others.” I assumed I was the cause of the mistreatment I received as a child and that I deserved it. As an adult, this led to feelings of powerlessness, helplessness, hopelessness, shame, vulnerability and oppression at the hands of others. The deceptions I told myself were:

“Poor me! Everything bad happens to me.”

“If other people would respond by valuing me, I would feel valuable.”

“People don’t value me therefore, I have no value.”

“No one cares about me.”

“No one can really help me.”

“I envy and resent those who seem happy and successful.”

“God is like everyone else – He will disappoint me.”

As a Victim, I believed I was at the mercy of situations or other people. Martin Seligman (1991) helped me understand my responses. He coined the term “learned helplessness” to describe beliefs about what contributes to successes and failures in life. Those with an optimistic attitude react to setbacks by:

· Presuming that they possess personal power to change things;

· Viewing negative events as temporary setbacks that are isolated to a particular set of circumstances;

· Believing negative events can be overcome by their effort and abilities; and,

· Deeming the causes of negative events as temporary.

Victims, on the other hand, react to setbacks by:

· Presuming that they are helplessness and that negative events are completely uncontrollable;

· Believing that the causes of negative events are permanent and will last a long time;

· Assuming that all efforts to create change will fail, so there is no motivation to try;

· Placing the fault or blame on others, excusing themselves and refusing to talk personal responsibility;

· Giving up easily;

· Using words such as “always” or “never”;

· Frequently feeling overwhelmed, depressed and unable to cope; and,

· Isolating themselves and hiding from life.

Basically, Victims believe that everyone else caused their misery and nothing they do will ever make a difference. All this inevitably leaves Victims feeling betrayed, angry, inadequate and taken advantage of by others, resulting in angry outbursts, isolation and loneliness.

This was my story for many years, as I lived out my mother’s message to me, “You are the cause of all the problems around here. We would all be better off if you weren’t around.” The deception that ruled my life emanated from the name I gave myself: “Ruiner of Relationships.” A victim mentality covered the deep shame of feeling unloved, unwanted, helpless and voiceless. Consequently, my relationships were fraught with difficulty. To release built up stress I used two of the four horsemen of the apocalypse (Gottman, 2015):

- defensiveness; and,

- stonewalling and hiding (Gottman, cited by Lisitsa, 2013),

However, these behaviour kept me stuck in a destructive cycle at the top of the volcano. As Maraboli (2021) aptly said, “The victim mentality will have you dancing with the devil, then complaining that you are in hell!”

Reflect…

Do you identify with the Victim role? How?

What deceptions are you believing?

The Rescuer

Photo by Andrey Kremkov on Unsplash

A Victim necessarily needs a Rescuer and I found one in my husband. The Rescuer or “Messiah” believes, “If I take care of others long enough, maybe they will care for me someday.” This rarely transpires, as those they are helping are usually Victims, unable or unwilling to care for themselves. Rescuers assume control by allowing themselves to be sacrificed by what appears on the surface to be caring for others. Socially, they are recognised for being selfless. However, the addiction in this role is a compulsive sense of responsibility that needs to rescue their Victims from pain and solve their problems. This assuages the Rescuer’s guilt and helps them to escape their feelings. Thus, we fit together like a hand in a glove!

The Rescuer regularly sacrifice their own needs and well-being by seeking out and attaching themselves to those whom they believe desperately need their help. This was true of my husband, the Rescuer, who craved feeling important and needed by me. However, rescuing and “fixing” me was really his attempt to vicariously resolve his childhood pain of not being loved and accepted for who he was, rather than what he could do. Even though he sometimes invaded my space, it occurred under the guise of helping me; for example, during a particular time of emotional fragility, he demanded I see a doctor specialising in restricted dietary solution for emotional problems. He tried to “fix” me. Rarely was he aware of the impact of this type of behaviour that kept me, as a Victim, dependent on him and gave me permission to fail. If he could focus his energy on my problems he did not have to address his own. Years later, when his care was not returned he fell into a time where he felt low and lacked direction. Some Rescuers can sacrifice themselves as martyrs by moving into the Victim role where they feel used and betrayed. Their refrain is, “After all I do for you, it is never enough,” resulting in a deep, angry resentment that surfaces at the top of the volcano.

Our marriage relationship, see-sawing around the top of the volcano for years, looked something like this: My husband, convinced he could heal me, himself and our relationship by fixing me, adopted a superior role that morphed into resentful anger when I resisted his help. I made sure he failed, as I lacked motivation to try and change things and refused to take responsibility for my behaviour. In fact, both of us were blind to our destructive cycle and harmful actions.

Reflect…

Do you identify with the Rescuer role? How?

What deceptions are you believing?

The Persecutor

Photo by Peter Forster on Unsplash

My mother was a classic Persecutor. A person who takes the role of Persecutor believes, “I get to feel safe by hurting others and intimidating them.” My mother’s identity revolved around the deception that someone else was responsible for her unhappiness. Persecutors like her usually feel like they are the Victim, which results in anger and the need for punishment of perceived wrongs. My mother was addicted to the feeling of an adrenalin rush she got through her angry outbursts and rage. She experienced a high from attacking and fighting, underscored by a compulsive need to hurt others. To release built up stress she used two of the four horsemen of the apocalypse: 1) blame and criticism; and, 2) attack and venting (Gottman, cited by Lisitsa, 2013). Persecutors like my mother alleviate their pain by punishing and inflicting it on others, but this keeps them stuck in a destructive cycle at the top of the volcano.

In the Persecutor’s world, my mother’s feelings of frustration triggered the right to get angry, rather than deal with personally uncomfortable or distressing feelings. She needed to see others as weak in order to prove to herself the truth of her destructive narrative about the world, that everyone was out to get her and she had to get them first. Shame and feeling “less than” were too painful, so my mother chose to become “better than,” with an aura of superiority. Her very judgmental and angry stance emerged when others failed to do or be what she thought they should do or be, according to her code of distorted thinking; for example:

“See what you made me do…”

“If it were not for you…”

“If only others would… the world would work.”

Persecutors like my mother feel frustrated when they cannot exercise control over themselves or others. Anger is the Persecutor’s energiser to keep anxiety and depression at bay. This defense mechanism not only keeps them in denial of their destructive behaviour, but they fail to take responsibility for it. Their behaviour is energised by a strong sense of entitlement, “You owe me,” and a willingness to go beyond acceptable behavioural limits, using verbal or physical force to get what they believe they deserve and have a right to have. The Persecutor’s constant need to be in control, to control others, and to use of verbal (and sometimes physical) force to stay in power can be annihilating for the recipient. This is profoundly problematic if one works, plays or lives with someone like my mother.

The sad part of all this is that my mother was unable to feel vulnerable and obtain the support she so desperately longed for when she experienced inner pain. She denied her own neediness, keeping others at a distance with angry, attacking outbursts. In her eyes, others were always in the wrong and her attacks were warranted and necessary to protect herself and stay safe. Persecutors like my mother, fail to see that they really believe others deserve the punishment they dish out and no one is allowed to challenge their authority. They alone demand to be right, because to face their own problems and behaviour would cause them to have to deal with their deeply distressing feelings of shame and to go there is too painful and anxiety-provoking.

So, my mother continued to rage against others until the day she died (she rang the Police repeatedly in the middle of the night from her nursing home to complain about being abused by the staff) and the destructive cycle repeated itself over and over again. Eventually, she was expelled from several nursing homes who were unable to manage her behaviour. She lived with an underlying fear of failure (that was denied). Perhaps her greatest fear was powerlessness that she could not deal with. Mostly, those who fly into rages “have low self-esteem and use their anger as a way to manipulate others and feel powerful” (Department of Health & Human Services, State Government of Victoria, Australia, 2018). In the final analysis, Persecutors such as my mother feel alone, unloved and unlovable.

Reflect…

Do you identify with the Persecutor role? How?

What deceptions are you believing?

Each of the three roles, Victim, Rescuer and Persecutor, keep us stuck in a destructive cycle at the top of the volcano and lead to poor relationships fraught with conflict. Beneath the “acceptable” persona that we present to our spouse and others lies a darker part: a wounded, sad, or isolated part of which we are unaware or ignore. Acknowledging and understanding the source of our particular role is the beginning of changing it. We discover that a healed wound can be a spring of emotional abundance and vitality, leading us towards healing and authenticity. Thus, the drama triangle identifies possible sources of adult anger.

What is Healthy Anger?

The roots of anger carried over into adulthood are often out of awareness. Nancie Carmichael (2011) maintains, “Wounds do heal, but there are times to allow the Great Physician to perform surgery so that they will heal right.” Psalm 139: 23 invites God to “Investigate my life, O God, find out everything about me; Cross-examine and test me, get a clear picture of what I’m about.”The primary root of anger is found in Genesis 3:1-6, where Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit and immediately experienced separation from God and each other. Now they had to hide. As a result, they moved from unity to distrust of each other. Shame engulfed them. They hid and defended themselves. To hide is to not show what we really think or feel. Ever since Adam and Eve fell, humankind dishonestly hides behind a self-protective mask or image, manifested in relational game-playing or getting angry.

A good place to begin when anger surfaces is to ask, “What goal has been blocked and who or what blocked it?” Then ask, “Is it deeper than that? Are there things from my past that are touched? How is my anger connected to an unhealed wound from my past?” If you are brave, ask those close to you, “How do I come across when I am angry? Do you see it emerging from something unresolved in me?” Let the responses move us toward repentance – the loss of what we depend on. Repentance involves an internal decision and an awareness that there is emptiness everywhere but in the Lord. It is a wilful ceasing of our pursuit of empty wells that hold no water and turning toward Jesus, the Source of Living Water. We typically grow and change when everything does not work, in our relationships or when suffering strikes. To walk in the Spirit means to do what is right out of choice, based on our belief in God’s perfect love to sustain us.

Therefore, what would it mean to enter the anger and embrace it? Begin by looking for strategies of responding to pain, loss or hurt with anger – internal decisions and self-protective patterns. These will be evident in current relationships. Ask Jesus where He desires change. This takes enormous courage and involves difficult, demanding and tiring work that requires a lot of attention. A trained counsellor can be of great help. As children, we did not have a choice in what happened to us, but we do now!

What is Anger that Honours God?

In Ephesians 4:26 God calls us to be angry, urging us to “be angry, but do not sin.” How is this possible? How do we know when anger is righteous or destructive? What helps me is a metaphor from scripture depicting anger as similar to a nose. In several places in the Old Testament, God is described with nostrils flaring at injustice. Psalm 18:8 describes God’s anger as, “Smoke rose from his nostrils; consuming fire came from his mouth.” The physical embodiment of anger and rage can be observed as heat, as in flared nostrils, snorting and a reddened face and nose or “his nose burned hot” (Maalej, 2004).

A contrasting image is found in Exodus 34 where God describes himself as, “slow to anger.” Exodus 34:6 says, “The LORD, the LORD God, merciful and gracious, longsuffering, and abounding in goodness and truth.” In Biblical Hebrew, longsuffering is literally translated, “long of nose”. Therefore, in contrast to a “hot nose,” God is “long of nose,” meaning that it takes much longer for his anger to ignite, as in Psalm 103:8, “The LORD is compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in love.”

Consider, what does “long-nosed” anger look like? In Ephesians 4:26 God urges us to be angry, “be angry, but do not sin.” How is this possible? The rest of the chapter gives us some clues. We are called to deal with it quickly, rather than holding onto it and allowing it to fester into bitterness that degrades others and gives the enemy a foothold. The sin is holding onto and nursing our anger. Ephesians 4:26-32 also cautions, “Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up according to their needs, that it may benefit those who listen” (v. 29). When Satan obtains a foothold, he urges us to use death words instead of life words; for example, Sam tells his daughter in anger that she is a useless waste of space. These are death words. We cannot unsay death words and they are just that – they cause soul death. Ephesians 4:31 urges us to “Get rid of all bitterness, rage and anger, brawling and slander, along with every form of malice.” Anger not dealt with leads to bitterness as a form of control. To sin in our anger is to hate vulnerability and love control.

To not sin in my anger is a tall order, perhaps because human anger is more concerned with us and our pride than it is with God’s righteousness (James 1:20). Righteous anger is “long nosed.” It sees the log in our own eye first (Mathew 7:5) It is guided by love and grief over injustice, but is “quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger” (James 1:19). It is more about God than about us. The only antidote for long-held anger is forgiveness, not because the person who hurt us deserves it, but because it is the only way to find release and peace. Thus, we are called to deal quickly with our anger and not give the enemy a foothold. Anderson (2000) writes:

We have all been victimized, but whether we remain victims is up to us. Those primary emotions are rooted in the lies we believed in the past. Now we can be transformed by the renewing of our minds (see Rom. 12: 2). The flesh patterns are still imbedded in our minds when we become new creations in Christ, but we can crucify the flesh and choose to walk by the Spirit (see Gal. 5: 22-25). Now that you are in Christ, you can look at those events from the perspective of who you are today… Perceiving those events from the perspective of your new identity in Christ is what starts the process of healing those damaged emotions.

How, then, do we express our anger? Anger seasoned with empathy, courage and compassion are more likely to lead to connection. Virginia Satir (1967, p. 73), a former family therapist, believes that a person who communicates in a healthy way can firmly state their case, yet at the same time clarify and qualify what they say. They always ask for feedback and are open and receptive to receiving it.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Closing Thoughts…

The Drama Triangle helped me to identify the deeply-held survival strategy of Victim. Thankfully, God gives us a way of dealing with anger in the Scriptures and longs for us to experience freedom from the ache of destructive anger.

Following the bruising interchange with a family member, for the first time I was able to step back and observe my behaviour from within, becoming both critical and compassionate towards myself. An inner dialogue ensued with God that went something like this, “God, help me to see what I am doing right now in response to this conflict. This is not the way I want to live. I need Your help.” In that moment He helped me harness the capacity for personal growth. Once again, I stood on the headland overlooking a turbulent sea and let go of the way I previously made sense of my world. God empowered me to rebuild my life in line with both His and my own authentic values. The process has taken years. It required courage and personal sacrifice.

A Declaration…

I declare that I have the mind of Christ. My mind is renewed to the ways of Christ. I take my angry thoughts captive and make them obedient to Christ. I put away all bitterness, wrath, and anger. I declare the peace of God over my life.

A Prayer…

O God of such truth as sweeps away all lies,

of such grace as shrivels all excuses,

come now to find us

for we have lost our selves

in a shuffle of disguises

and in the rattle of empty words.

We have been careless

of our days,

our loves,

our gifts,

chances…

Our prayer is to change, O God,

not out of despair of self

but for love of you,

and for the selves we long to become

before we simply scuttle away.

Let your mercy move in and through us now…

Amen.

(Ted Loder, 2013, My heart in my mouth: Prayers for our lives)

About the author: Dr. Paula Davis is a clinical counsellor, supervisor and educator specialising in psychological trauma. She has worked in higher education over many years as senior lecturer in counselling. Along with her husband she designs and delivers marriage enrichment/education programs in Australia, Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Europe.

References

Anderson, N. T. (2000). Victory over the darkness: Realizing the power of your identity in Christ (10th ann. Ed.). USA: Regal.

Berry, C. R. (2003). When helping you is hurting me: Escaping the Messiah trap. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company.

Brown, F., Driver, S. R. & Briggs, C. A. (1951). A Hebrew and English lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Carl Jung. (2019). Goodreads. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/290581-a-man-who-has-not-passed-through-the-inferno-of

Carmichael. N. (2011). God heals all wounds. Thoughts from the Porch: Encouraging Thoughts for a Busy World. Retrieved from https://aprilhawk.wordpress.com/2011/10/24/god-heals-all-wounds/

Department of Health & Human Services, State Government of Victoria, Australia. (2018). Anger – how it affects people. Better Health Channel. Retrieved from https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/anger-how-it-affects-people

Freyd, J. (2002). In the wake of terrorist attack, hatred may mask fear. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 2(1), 5-8.

Gottlieb, M. (1999). The angry self: A comprehensive approach to anger management. USA: Zeig, Tucker & Co.

Gottman, J. (2007). Why marriages succeed or fail: And how you can make yours last (1st ed.). USA: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

Gottman, J. (2015). The seven principles for making marriage work. USA: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale.

Harper Nichols, M. (2020). All along you were blooming: Thoughts for boundless living. Grand Rapids, MG: Zondervan.

Johnson, S. (2018). Escaping conflict and the Karpman drama triangle. Retrieved from https://bpdfamily.com/content/karpman-drama-triangle

Keller, T., & Keller, K. (2011). The meaning of marriage: Facing the complexities of commitment and the wisdom of God. UK: Hodder & Stroughton.

Knoll, M. (2003). Bread and wine: Readings for Lent and Easter. New York: Orbis Books. Lisitsa, E. (2013). The four horsemen: Criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. The Gottman Institute. Retrieved from https://www.gottman.com/blog/the-four-horsemen-recognizing-criticism-contempt-defensiveness-and-stonewalling/ Loder, T. W. (2013). My heart in my mouth: Prayers for our lives. Oregon, USA: Wipf and Stock.

Maalej, Z. (2004). Figurative language in anger expressions in Tunisian Arabic: An extended view of embodiment. Metaphor and Symbol 19(1), 56.

Mathias, A. (2011). Biblical foundations of freedom. Internet: Wellspring Publishing.

Nouwen, H. J. M. (2014). A cry for mercy: Prayers from the Genesee. Australia: Rainbow Book Agencies P/L.

Satir, V. (1967). Conjoint family therapy. USA: Science and Behavior Books, Inc.

Seligman, E. P. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Simon, P. (1973). Something so right [Lyrics]. Retrieved from https://www.paulsimon.com/track/something-so-right-4/

Walters, R. P. (1981). Anger, yours and mine and what to do about it. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

Wright, N. (1976). Communication: Key to your marriage. CA, USA: Regal Books Division, G/L Publications.