By Dr Paula Davis

15 October 2025

“Communication is to a relationship what breathing is to sustaining life.” — Virginia Satir

“Like a splinter needing extraction from the flesh, removing the source of your pain may cause more pain – but then real relief.” — Author Unknown

“Now I know in part; then shall I know fully, even as I am fully known.” — 1 Corinthians 13:12

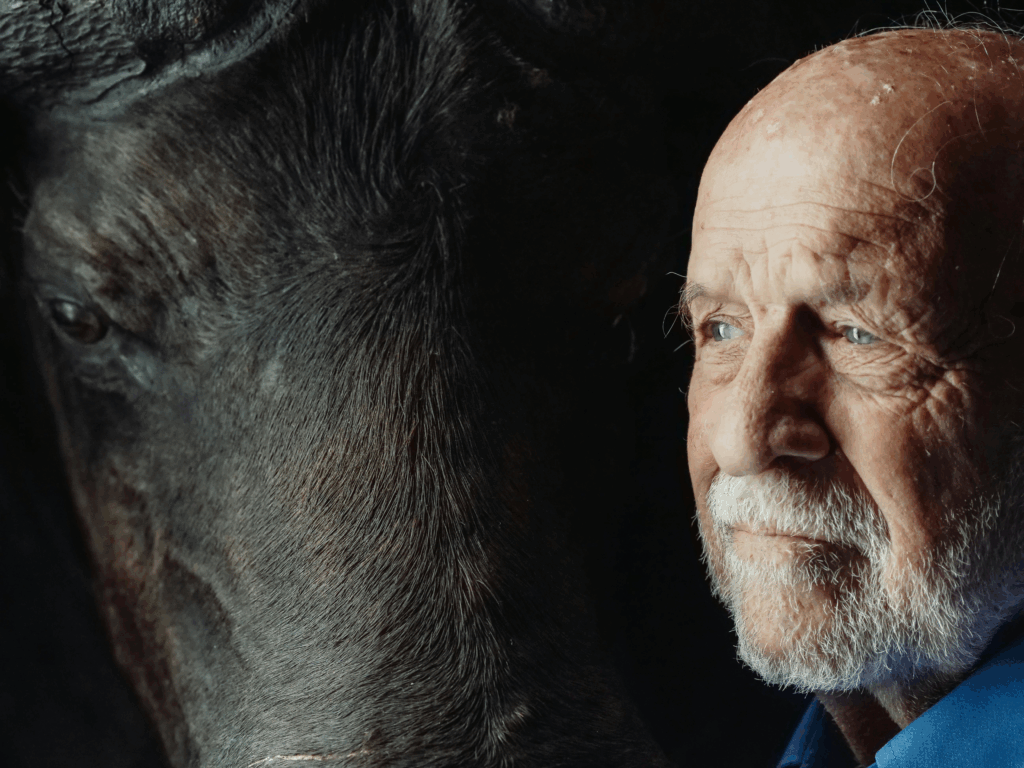

Photo by Kindel Media: https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-in-blue-shirt-beside-black-horse-8172812/

Naming the Longing at the Heart of Our Stories

There is a moment, often small and easily missed, when a child turns toward a caregiver with wide, searching eyes and silently asks: Do you see me? Not just, Are you watching? but something far deeper: Do you delight in me? Am I known here? Do I matter? Long before we can name it, we ache to be seen.

It is a longing etched into our design, rooted in our creation by a God who sees, knows, and calls us “very good.” We are born for connection, not just biologically but spiritually, for relationship with a God who formed us in love, and with others who mirror that love in their gaze, touch, and presence.

Yet for many of us, that ache has gone unmet. Or worse, it has been exploited, dismissed, or shamed. In my own story, I carried this ache for decades, hidden beneath performance, people-pleasing, and perfectionism. I longed to be enough, to be chosen, to be cherished. But somewhere along the way, I began to believe I had to earn being seen. That love came with conditions. That if I was too emotional, too messy, too much, I would be abandoned.

Perhaps you carry that story too. Perhaps you learned early on to silence your voice, to toughen your skin, to make yourself smaller or stronger so you wouldn’t be hurt. Perhaps you heard, in subtle or overt ways, that to be truly known was to risk rejection.

But the truth is this: the longing to be seen is not a weakness. It is the birthplace of intimacy. We cannot love or be loved without vulnerability. We cannot heal without being known.

This article will explore:

- The ache to be seen is holy, not shameful.

- Early experiences of misattunement or emotional absence shape our adult relationships.

- Being truly known by God, others, and ourselves is a significant aspect of human existence.

- Naming the ache and stopping apologizing for it is a threshold that can be crossed.

This is not just a psychological journey. It is a sacred one. Because when we come to Jesus with our ache, to be seen, understood, and held, we discover that He has been turning toward us all along. He sees us. And He calls us by name.

Deceptive Beauty

The beauty of Mullaitivu, a coastal town in northern Sri Lanka, is deceptive. Each morning, we drive to the training venue along a road that skirts a shimmering lagoon. In the evenings, we return, mesmerised by the aching beauty of the sunset reflecting off the water, its fleeting, breathtaking colours holding back the encroaching darkness.

But beauty here does not erase brutality. The war has ended, yet the wounds remain raw. Not long ago, this road was lined with bodies. Thousands died in this very lagoon, trapped between advancing forces and the last rebel stronghold. Fathers, desperate to save their families, dragged them into the water, only to be swallowed by the tide. Many could not swim. The rebels, in turn, used civilians as human shields, just one of many war crimes etched into this scarred land.

We are taken to see the “sights.” But devastation is a more fitting word. Suffering is not easy on the eyes. It feels surreal. like we’re driving through the set of an apocalyptic film. Tree stumps stand like stunted sentinels, sheared off by relentless bombings. The ground is torn open, cratered with deep gashes now filled with monsoon rain. From a distance, they look like lakes, until you look closer. The earth is littered with remnants of shattered lives: rotting clothes in bright colours, scattered utensils, broken toys, meagre valuables. All mingled with buried dreams.

And then I see them, dark-skinned human wrecks, brutalised souls sifting through the ruins, searching for fragments of a life stolen from them. Our van slows, and I wish it wouldn’t. Silent screams rise in my throat. I don’t want to be a spectator to this misery. Does God see this? Is His heart sickened by these killing fields?

I want to turn away, to return to the safety of my life in Australia. But how do I ever unsee this? I remember: “When He [Jesus] saw the multitudes, He was moved with compassion for them, because they were weary and scattered, like sheep without a shepherd” (Matt. 9:36). He didn’t turn away. He looked suffering in the face and entered into it. Can I do the same?

The deeper we travel into the war zone, the more my body revolts. My stomach churns. My head pounds. Nausea rises. My body carries the weight of my heart’s grief. I want to scream. But my voice fails me. I am a middle-class Australian, born and raised in political security. How do I even begin to process this horror?

My gut twists against the injustice. These tattered clothes belonged to people. People with stories. With laughter. With love. I feel it deep in my bones, we were not made for this.

By the roadside, a burned-out van lies half-buried, overgrown with grass, as if nature itself is trying to cover its shame. The boy driving us translates the faded words on its side: Ice Cream Vendor. The irony is cruel. Once, this van was part of ordinary life. Now, ordinary life is gone. No birds sing. No dogs bark. This is a wasteland.

A little further, we pass a graveyard of vehicles, buses, trucks, tractors, twisted metal heaped like war’s leftovers. And yet, among the ruins, some families have returned, stubbornly rebuilding. Their resilience stirs something deep in me. So much has been lost, so many lives, so many dreams crushed. And still, they rise.

This is the backstory to what comes next.

Broken and Brittle

It’s the beginning of our first trauma recovery program in this war-scarred land. We stand before people shattered in body and spirit; their pain carved into vacant faces. How do you live with what the eyes have seen? Some are blinded by bombs. Others paralysed. A beautiful young woman bears the cruel imprint of bullets lodged in her spine. One side of her body is lifeless. All have lost someone. Some wear scars on the outside. All carry them within. Their hollow smiles break me open. I want to retreat, curl up in a corner and weep. But not yet. The work is not done.

My task is to bear witness. To hold space for their suffering. To offer, if only a flicker, some hope. To bear witness is to engage in a social process that unveils concealed realities of wickedness and suffering, becoming a therapeutic act in itself. It’s not about what we say, or do, or touch, it’s about presence. Our interconnectedness means that witnesses will carry a portion of the emotional burden, even in silence (van Dernoot & Burke, 2009).

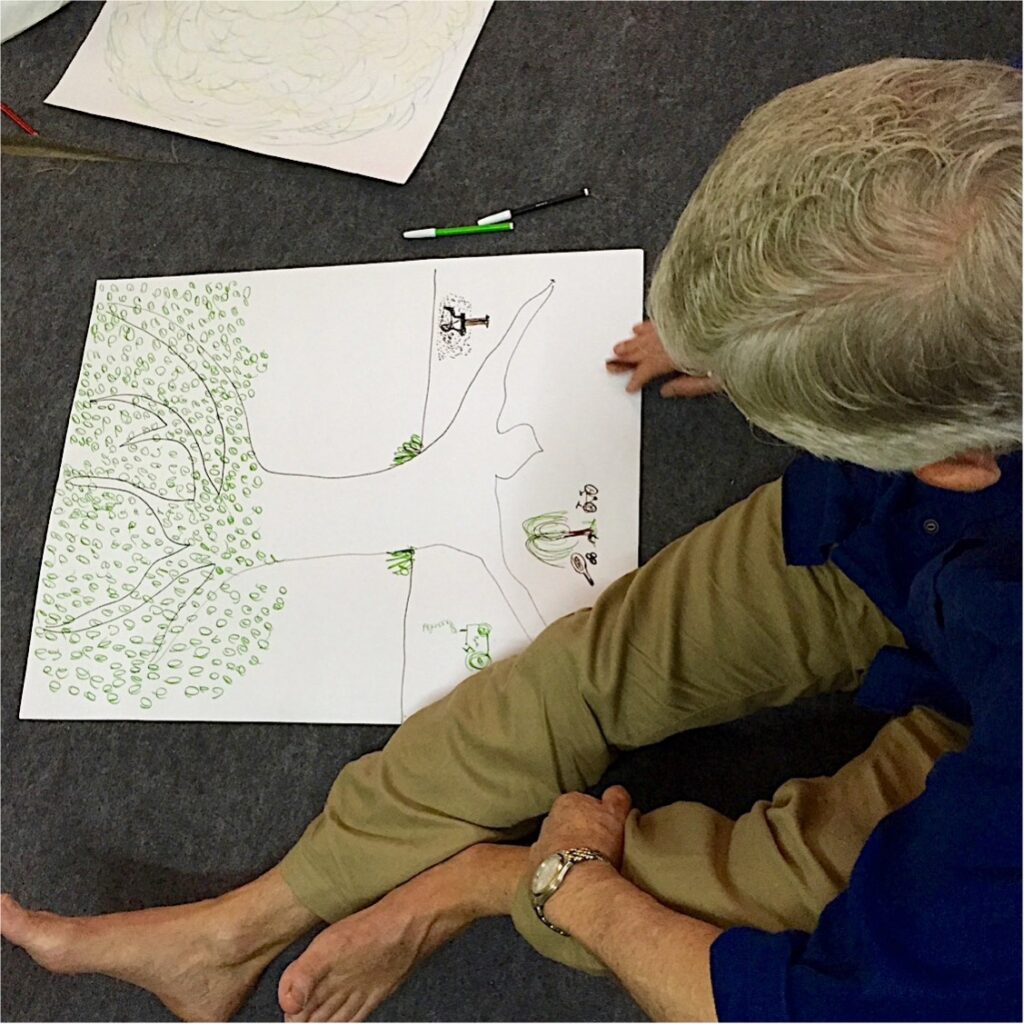

On the second day, participants begin drawing a tree, an exercise from Narrative Therapy called The Tree of Life (Ncube, 2006). Roots symbolise family, culture, history. As they draw, something shifts. Their hands move gently, creating beauty where there was none. A quiet balm begins to soothe their souls.

Then she gives me a gift. I don’t recognise it yet. I sit beside her. Her paper is mostly blank. The tree is there, but no words, no roots. Her head slumps into delicate, coffee-coloured hands. Blue-black hair veils her face. Her exquisite femaleness folds in on itself.

“I can’t draw my roots,” she whispers, “because they are so broken.”

Time slows. Something inside me splinters. The pain is sharp, slicing into long-buried places.

I steady myself. Finish the session. But something in me has come undone. I long to disappear into silence. But I know that isolation is fertile ground for festering wounds. Perhaps healing comes not in retreat, but in opening, to grace, to connection, to giving what I long to receive.

What I am experiencing has a name: Vicarious Trauma. The pain of others takes root in my own body, echoing their horror inside me. Johnson (2009) reminds us that trauma strips away our capacity to regulate emotion. We drown in it, or we shut down. “Pain has a way of clipping our wings… and if left unresolved, you can almost forget that you were ever created to fly” (Young, 2008).

I am drowning. But worse still, hurt people hurt people. That’s exactly what happens next.

A Smouldering Wick

That evening, my exhaustion spills out sideways. I’m irritable. Fragile. My words snap. The man I love bears the brunt. He doesn’t deserve it. But neither do I know how to stop it. I am weary, body and soul. Frayed at the edges. And all my defences, my empathy, my patience, my grace, collapse under the weight of the day.

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko: https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-burnt-candle-wick-in-close-up-shot-7033937/

Later, I lie in the dark and ache with guilt. Why am I like this? I’ve just spent hours holding space for the broken, yet here I am, hurting the one who holds me. This is the paradox of compassion fatigue. You pour yourself out until you are empty, and then, even your love becomes brittle. It’s here that shame seeps in.

Not long after, I wake in the middle of the night, sweating. Shaking. I am disoriented. I can’t breathe. My chest is tight, my thoughts spiralling. The weight of all I’ve seen presses down like a tombstone. I reach for prayer, but even words feel foreign. Something is happening in my body. I know the symptoms. I’ve counselled others through them. But now I’m the one coming undone.

This is trauma. Not my trauma, but theirs, woven into mine. Secondary trauma, they call it. But there’s nothing secondary about it when it’s your soul unravelling. Still, a whisper comes in the dark: “A bruised reed He will not break, and a smouldering wick He will not snuff out” (Isaiah 42:3). It’s tender, almost imperceptible. But it finds me. God does not shame the weary. He restores them.

The next morning, I sit quietly before our training begins. The young woman with the half-drawn tree enters the room. Our eyes meet. She smiles, not a hollow smile this time, but one with depth. Then she offers me something wrapped in paper.

Inside is a tiny handmade notebook. The front cover is decorated with a single word written in Tamil script. “What does it say?” I ask softly. She hesitates, then whispers: “Hope.”

I am undone.

This woman, traumatised, violated, silenced, has reached through her pain to give me what I didn’t know I needed. Not advice. Not theology. Just hope. She becomes my teacher.

Where the Vows End and the Real Story Begins

Mullaitivu was a repeat of sorts of our wedding day.

A wedding can feel like inheriting a vast mansion with many rooms, each one full of promise. We enter marriage believing we’ll explore those rooms together, uncovering their richness and mystery over time. But as the years unfold, we begin to discover that some doors remain closed, locked by fear, past wounds, or unspoken pain. Attempts to open them can bring frustration, failure, and hurt. Eventually, we learn to live only in a few familiar rooms, leaving the rest of the house, its unexplored intimacy and potential, abandoned.

Early in our marriage, my husband and I locked certain doors because it felt too risky to open them. We weren’t ready to step into the mess of knowing and being known. But over time, through our work with couples, we’ve learned just how common those locked doors really are.

They take many forms:

Finances and spending

Deep emotions – joy, fear, pain, or anger

Equality in decision-making

Touch, affection, and intimacy

Extended family dynamics

Division of domestic responsibilities

Religious faith

Conversations about death

Locked doors can break a marriage. And when a marriage breaks, the people within it break too. It’s like trying to separate two halves of an orange; it never happens cleanly. The tearing leaves behind lost history, fractured dreams, and a painful longing to know and be known.

We often hear couples say: We just don’t communicate anymore. But in truth, they communicate all the time, through silence, body language, and routine. The real issue isn’t what is said, but what remains unspoken. What they are too afraid to voice. What they don’t want to hear.

Communication, by itself, isn’t a virtue. It only matters when we’re willing to speak the truth in love, not because it’s easy, but because, if we don’t, the distance between us will widen until we feel like strangers in our own home. True communication is more than words. It is the willingness to reveal ourselves, to be heard and understood at the deepest level.

Communication is to love what blood is to life.

The Key to the Locked Door

Photo by Forest Plum on Unsplash

There were times when it felt like we were locked out of our own house. Too many rooms were off-limits. Too many silences stretched between us.

But years into our marriage, we found the key: the art of revealing ourselves. Just as God reveals Himself so that we might know Him, we discovered we needed to risk the same transparency with each other.

In the aftermath of Mullaitivu, we were nursing invisible bruises. The trauma we witnessed there battered us, but the deeper wound was what happened between us. We returned to Australia feeling as if a knife had been lodged in our hearts. We didn’t want to go back to Sri Lanka. We didn’t want to minister again. And we didn’t know how to bridge the growing gap between us.

Counselling helped us trace the fracture to its source. There’s an old Kalenjin proverb from Kenya: “We should talk while we are still alive.” So, at a marriage retreat, we talked. And we listened. We began to realise that not knowing ourselves, our wounds, longings, and fears, posed a significant risk to our marriage as well as to our ministry. People who engage in destructive behaviour often begin by fragmenting themselves, hiding from the truth of their actions and emotions. In the words of Rebecca Solnit (2014), their internal landscapes become “caves, minefields, and blank spaces.”

But in choosing to come alive again, to return to our painful emotions rather than avoid them, we found grace. The seeds of willingness bore sweet fruit. And slowly, the doors that had been locked for so long began to open.

The Healing Power of Connection

God is a relational being (Genesis 1:26), and our ability to form deep, sustaining relationships is both a reflection of His image and a marker of emotional and spiritual health. But since the Fall, shame drives us into hiding. Relationships, rather than being places of refuge, become sites of conflict and fear. And yet, God’s heart is always for restoration, for reconnection, for closeness, for knowing and being known.

Secure, loving connection is more than emotional comfort; it is essential for healing and growth. Research confirms this. Even in the face of chronic illness, war, or abuse, people who maintain strong, emotionally significant relationships demonstrate greater resilience (Van der Kolk & McFarlane, 2006).

When trauma floods the body with helplessness and fear, it fractures our sense of self and makes the world feel chaotic and unsafe. But a secure, comforting connection, what attachment researchers call a safe haven, is an antidote. It soothes, strengthens, and rebuilds our capacity for trust and emotional regulation (Johnson, 2005).

Yet trauma also presents a painful paradox: the deep need for closeness coexists with a profound fear of it. We long for connection but remain vigilant for danger. These competing forces create confusion, making even loving relationships feel unsafe. My husband and I didn’t understand this tension for many years, and in that misunderstanding, we lost our way.

Closing Thoughts

We were created for closeness. One of our deepest longings is to be seen, known, and accepted. Our most formative experiences, marriage, friendships, the birth of children, even death, are shaped by connection. These are the places where we come face to face with love, with grief, with our own vulnerability.

Locked doors, those places of silence and fear, can only be opened through courageous communication and compassion. True connection requires vulnerability. We cannot fully know ourselves in isolation, and we cannot truly know another unless we are willing to be seen. Without that, we stay hidden behind walls, longing for intimacy but terrified of what it might cost.

Longing to know and be known isn’t about acts of service or managing a household. It’s not about picking up after our spouse or suppressing our needs. It’s not about preserving harmony at the cost of truth.

It’s about giving each other the courage to become the man or woman God is calling us to be. It’s about change, disruption, and growth. It’s about God breaking into human lives and reshaping us through love. And that reshaping often begins with honest words, offered in safety.

Knowing and being known is not passive.

It is active, brave, and messy. It calls us forward into deeper intimacy with God and each other. It invites us to risk, to speak, to listen, to reveal, to receive. This is the ongoing work of love.

This is the way the doors begin to open.

Prayer

Heavenly Father, Give me the courage to make myself known to those who love me, to step beyond fear and into vulnerability. Help me to listen deeply, to see beyond words, and to seek to truly know the hearts of those around me. Teach me to love as You love, with grace, patience, and understanding. May my relationships reflect Your truth and be places of healing, restoration, and deep connection. In Jesus name, Amen.

Reflection and Discussion

What rooms in your “house” remain closed, either in your marriage or in your relationship with God?

What fears or beliefs keep those doors locked?

When have you experienced the pain of being unknown or misunderstood in a close relationship, and what impact did it have on your ability to connect?

What does “speaking the truth in love” look like for you right now?

How can you practice it with compassion?

Consider a time when someone created a “safe haven” for you. How did their presence help you heal or grow?

About the Author

Dr. Paula Davis, a clinical counsellor , supervisor and educator with three advanced degrees, specialises in trauma counselling, and before she retired, was a senior lecturer in counselling, designing and delivering curricula. Her book, “Eating Water, Drinking Soup: Finding Nourishment in the Deepest Pain” is available on request. With her husband, she delivers marriage programs internationally. In 2021, they published “A Safe Place: A Marriage Enrichment Resource Manual” available on online bookstores. Paula has published articles in peer-reviewed journals and speaks at conferences and venues in Australia and internationally.